By Alicia M. Bertrand, M.A.

March 24, 2024

Peterborough’s courthouse has stood atop a hill overlooking parts of downtown Peterborough and casts a sense of authority over its citizens since 1842. The courthouse is one of the earliest courthouses constructed in Ontario. The threat of solitary life in a tiny jail cell of the Peterborough County Jail behind the courthouse enforced social norms and behaviours on the townsfolk. The County jail was home to petty criminals, mostly citizens who had the misfortune of being impoverished or mentally ill. Throughout its existence, the jail has had issues in governance, population, jailbreaks, and other issues. Although most inmates spent short sentences at the County jail, five men faced the gallows and the end of their lives there over its 160-year span. Each man was found guilty of murder, but the circumstances surrounding each murder were vastly different. This article contains their stories as well as a concise history of the courthouse and jail. Unfortunately, for those crime history fans who would like to visit the Peterborough County jail, only partial walls and historical plaques remain. Why was it partially demolished? A riot in 2001 sealed the jail’s fate before being abandoned and inevitably ruined beyond repair. The courthouse and jail hold as many fascinating stories as they have prisoners throughout time.

The Property

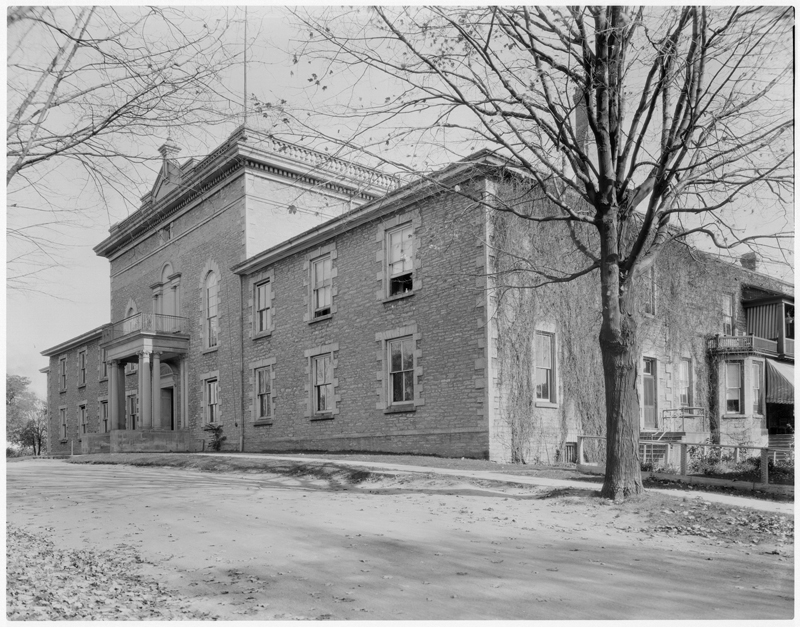

In June 1838, the district magistrates, with the Honourable Thomas A. Stewart presiding, authorized the construction of a courthouse and jail in Peterborough. Peterborough became the district town of the District of Colborne earlier that year. Architect Joseph Scobell designed the courthouse.[1] Sir George Arthur, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada laid the cornerstone of foundation for the courthouse on August 25, 1838.[2] The construction of the courthouse and jail cost £7000. Most of the funds were generated from local wealthy families, the Bank of Cobourg, and local taxpayers.[3] Scobell’s design featured Classical Revival and Georgian elements, a central cupola and a pedimented portico with Ionic columns.[4] To add flair to Scobell’s design, the building committee requested that the local masons hand-carve the window surrounds and decorative quoins.

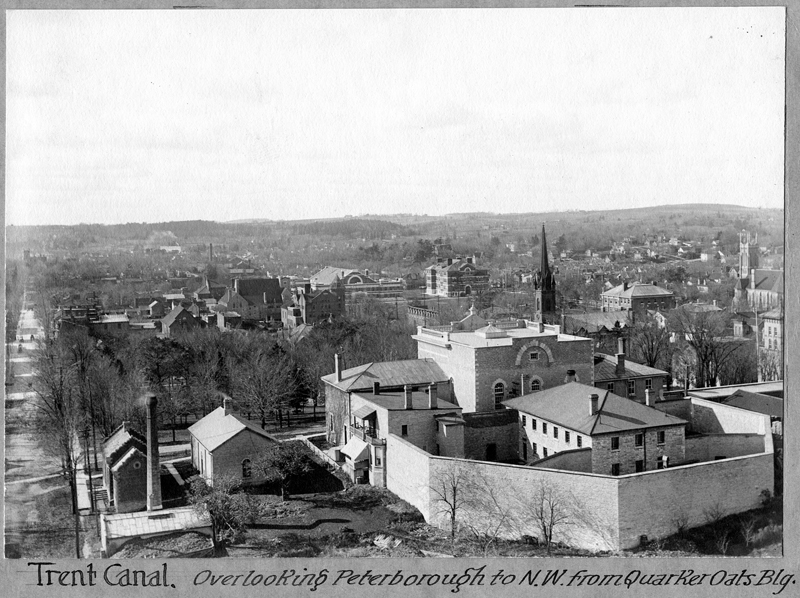

The courthouse and jail stood at 470 Water Street at the top of the hill between Murray St. and Brock St., overseeing Courthouse Square (which became Victoria Park), which spans from the front of the courthouse to Water St below. The park was based on the Victorian style of tree-lined geometric parks with a central fountain meant to encourage social interaction and public recreation.[5]

The jail was built behind the courthouse with the eastern wall facing the Otonabee River. Local masonry workers quarried limestone from Peterborough’s Jackson’s Park to build the jail portion of the courthouse in 1842.[6]

The majority of inmates in the Peterborough County jail were persons charged with petty crimes, such as drunkenness, shoplifting, homelessness, and those who had defaulted on loans. In the 19th century, poverty was the cause of many incarcerations in Peterborough.[7]

Renovations

John Belcher, the architect of Peterborough’s Market Hall. P.C.V.S., etc., renovated the interiors of the courtrooms in 1878-79. His goal was to increase light and airflow to the courthouse. He accomplished this by removing the cupola in the courtroom and raising the ceiling. The east wall was moved further into the jail section and four skylights were added to the courtroom. This also allowed for more seating and viewing gallery space. Belcher’s renovations included ornate oak seating, tables, and the prisoners’ box.

Further additions and renovations to the courthouse, jail, and administration buildings on the property, as well as landscaping and construction in Victoria Park, include William Blackwell, a prominent Peterborough architect in the late 19th century and early 20th century, and Eberhard Zeidler, the German-born architect who trained at the Bauhaus. Blackwell renovated the courthouse in 1916 after the Quaker Oats factory fire and explosion damaged the courthouse. Courtroom One was renovated at that time, as well as the roof. The original craftsmanship of plaster, woodwork, and millwork was kept intact during this renovation. Zeidler added a modernist addition in 1959.

In 1863, T. F. Nicholl, the County Engineer, in partnership with the provincial government’s prison architect, H. H. Horsey, who designed several county jails in Upper Canada, designed a newer and bigger jail. This jail was attached directly to the courthouse. Construction was completed in 1865. The jail now provided higher walls and an administrative pavilion fronting a cellblock of back-to-back, narrow cells which borrowed its design from Kingston Penitentiary. The jail also housed the Sheriff and jailer in this new two-storey rectangular building.

Jail governance and conditions

The following stories are presented in chronological order. The stories may help the modern reader understand the conditions the inmates lived in, but also the governance and structure of the jail.

In July 1856, a woman named “O’Brien”, while serving a term for larceny, was “seduced” (possibly raped) by a jail guard at the Peterborough County jail and gave birth to a child. The Peterborough Examiner reported that the matter was “privately investigated” and that they “trust…he will be able to afford such an explanation as will free him from all blame”.[8]

In 1862, the Peterborough County Grand Jury ordered a more suitable jail structure to be erected to enhance the governance of the inmates within. Canada dove into the new Auburn Plan, first instituted in the Auburn Penitentiary in Auburn, New York, which had a philosophy of incarceration that included reform through silence, isolation, religious training and hard labour. This philosophy was believed to help inmates develop personal discipline, a hard work ethic, and respect for authority. The Auburn Plan also set guidelines for governance for the Sheriff and jailer. They would now classify inmates by age and the severity of their crime. The Auburn Plan remained the standard institutional philosophy in the United States and Canada until about 1930.

In 1872, The Peterborough Times reported that the County Council had denied prisoners hard labour by “neglecting to provide the means for carrying out the requirements of the law”. It was suggested that the prisoners should break stone, or chop wood for the courthouse and jail.[9]

By 1934, Provincial Jail Inspector James A. Norris and Provincial Secretary Hon. G. H. Challies reported that upon their tour of provincial jails, Peterborough County was one of four that were “quite unsatisfactory”. The three other jails had managed to clean up their act and their jails. However, Peterborough County’s officers who promised that the “secure place of restraint, food, clothing, and health conditions” would be improved had failed. Norris and Challies threatened the officers with suspension if the issues were not dealt with. Most telling, Norris reported that “The male prisoners are compelled to sleep on straw mattresses on the floor and the blankets on being examined were found to be dusty and dirty.”[10]

On a lighter note, in 1939, after a young man from Lake Penage spent some time in the Peterborough County jail on a vagrancy charge, he sent a letter to the officials that said “The worst feature of your hotel is the lack of reading matter”. In the letter, the former inmate included a five-year pre-paid subscription to a magazine.[11] At least the Lindsay jail has a library!

In 1953, prisoners of both Lindsay and Peterborough County Jail complained to the legislative committee that their food needed more seasoning. However, W. J. Stewart, PC, Toronto-Parkdale claimed that meals were not allowed to have pepper added, or pepper shakers, out of fear that inmates could “throw it in the eyes of the guards”.[12]

The County jail was not large enough to house mass groups upon arrest. This was evident in two incidents in the 1960s. In 1961, Peterborough County Jail Governor John Weyer told Peterborough City Council that the jail may need an extension. He reported that in a space meant for 24 inmates, the jail had recently housed 50 inmates. He said that in the six months prior, the average occupancy in the jail was 32. It was so overcrowded that sometimes the guards had to allow the inmates to sleep in corridors, or there were six inmates per cell.[13]

In 1966, 26 people were arrested for picketing at the Tilco Plastics strike. One of the arrestees, George Rutherford, Executive Officer of the Peterborough and District Labour Council, spent five days in the County jail before being transferred to Millbrook Correctional Facility. He noted that the “old building was never meant for [that] size of a crowd. They did not have enough blankets to go around and they had to send out for more beans and bread the day we landed.”[14]

During an Ontario Legislature session in June 1966, Liberal Leader Andrew Thomson asked Minister of Reform Institutions Allan Grossman why, in the past two and a half years, 50 persons under the age of 16 were “locked up” with adults in the Peterborough County Jail. Grossman was unsure, as he noted it was a “municipal” issue, but that some smaller jurisdictions didn’t have any other facilities.[15] Even in 1981, Judge L. T. G. Collins sentenced 16-year-old Michael McNamara to serve seven days in the Peterborough County jail for a possession of marijuana charge. People were shocked, even the jail officials, who sent him to a Salvation Army halfway house instead of having the teen endure a week in jail.[16]

Although it was determined that the staff and officials were not at fault, an inmate died of typhoid fever in 1957. The 44-year-old Curve Lake resident Clayborne Taylor, was serving a sentence in the Peterborough County jail when he complained of feeling ill. The jail nurse treated him for influenza, but he got worse and was sent to Civic Hospital. He was sick for three weeks before the hospital diagnosed him with typhoid fever. However, he died the day his diagnosis was determined. If the officials had sent him to Civic Hospital sooner, would he have lived? What were the conditions like in the jail at that time, let alone throughout time? Without more primary sources, it’s hard to know.[17]

Jailbreaks

The following stories are presented in chronological order.

At 3 a.m. on June 4, 1898, Sergeant Nash and Officer Reid caught James Macdonald, a.k.a. Mart Marshall, and James Fobes in the west end of Peterborough after they escaped from the Peterborough County jail earlier that evening. Macdonald had been convicted of burglarizing the Norwood post office and carrying nitroglycerine (an explosive). He escaped while awaiting transfer to Kingston Penitentiary for a 14-year sentence.[18]

In 1914, George Coates, a.k.a. John Clarke, escaped from the Peterborough County Jail, but his travels were cut short when he tried to jump on a Grand Trunk Railway train and had his legs amputated by the wheels on the track. He was rushed to Parkdale Hospital in Toronto, near the Swansea station where the accident occurred, but died from his injuries.[19]

On May 17, 1925, 28-year-old Isaac Mitchell Sellyeh broke the door of his jail cell and stole keys to the store room. He took a rope from the store room, snuck through the women’s ward, threw the rope over the exterior wall, and escaped from the Peterborough County jail. He had an issue with his right leg, but his obvious limp did not impede his escape. He was caught by a keen-eyed Bancroft citizen who had picked Sellyeh up as he hitchhiked to Marmora. Sellyeh was in jail serving a six-month sentence for fraud and theft.[20]

In January 1929, 23-year-old James Parks escaped the Peterborough County Jail, stole a car, and went on a five-month-long police chase through Ontario. He was finally caught in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan in May. He was then sentenced to five years in Kingston Penitentiary, which must have set him off. Between Windsor and Kingston, he attempted to get free from his leg shackles and jump off the train several times. Along with Parks, J. Williams and Milo Prosser also escaped but were caught sooner than Parks. [21]

In April 1941, Lawrence Burns, Thomas Nicholls, Louis Gallow, and William Bradd cut a hole through a brick wall and got into the outdoor corridor of the jail. While they were sawing through the bars on a window that faced the prison yard, they were caught by a guard and sent back to their cells.[22]

On May 20, 1943, two prisoners, Alex Zolomy and John Sercoski, hit a guard in the head with a metal bolt wrapped in cloth and stole the guard’s keys. They attempted to flee through the jail yard but were apprehended as they tried to climb onto the roof of the South Wing of the building. The guard was taken to the hospital due to cuts to his head but was otherwise alright.[23]

In 1968, 23-year-old Keith Lindsay Lawrence decided he didn’t want to be transferred to Kingston Penitentiary for break-and-enter and armed robbery, so he sawed through the bars, climbed the wall of the Peterborough County jail, and fled. He surrendered after 9 months to the police in Windsor.[24]

In September 1992, Leslie Lafont mirrored James Parks’ escape. While Lafont awaited trial for burglary charges in the Peterborough County jail, he climbed over the razor wire-topped wall in the recreation area of the jail. He stole a car and fled. He was caught, like Parks, in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan after a few days.[25]

Hangings

[The following stories are presented in chronological order. These stories are excerpts from my currently unpublished book, “That Doesn’t Happen Here” Small Town Ontario Murders, Pre-1950. For more information, email alicia@ancestrybyalicia.ca]

William Brenton

Jeremiah Payne and his new bride were only 22 and 21 years old when they established a farm in Dummer near the head of Stoney Lake when it was still an isolated area.[26] Two years later, in 1872, the Payne family hired William Brenton after he was employed by Jane’s father, Frederick Miles. Although Brenton was noted by neighbours as “giving frequent exhibitions of morose and vindictive temper”, the Paynes’ never suspected Benton to deserve the noose.[27]

On November 14, 1872, Jeremiah Payne left the farm to go to a threshing bee at the Sutton’s farm. Brenton had come to see Payne and asked him if he could be finished for the day after he built a root house on the Payne’s farm, and wanted to be paid. Payne said that he was in the middle of threshing and he would not be home for a while. Whether this was a trigger for him in anger towards Jeremiah Payne, or if he wanted to see if Payne would return home in the next few hours, we may never know. However, what happened next was a display of violence and horror.

Brenton returned to the Payne farm and attacked Jane Payne. The Peterborough Times reported that Payne was found only a few feet from the front door, in a position that clearly showed she attempted to get away from her attacker. She had “her head beaten to a jelly and her throat cut”.[28] The iron part of a pick axe was found covered in blood beside her body. 12-year-old David Doughty, who had been living with the Payne’s as a work arrangement for their cousins, was found in the root house with his throat slit.[29] The handle of the pick axe which Brenton used to build the root house, was found near Doughty’s body. The Payne’s 10-month-old daughter, Ann Eliza, was left unharmed in the cradle.[30] The Chicago Tribune also reported that Jane was pregnant. Dr. Kincaid promptly performed an investigation of the scene and autopsies on the two victims.[31]

The threshing mill had broken down, so Payne and two neighbours returned to their homes. When Payne screamed upon finding his wife’s body, the neighbours who heard him ran towards the farm. Payne also realized that his rifle, ammunition, and other items, were stolen from the house. Payne immediately alerted the police and suspected Brenton.

Brenton was found by local citizens who were on alert. The police were quickly called to arrest him so that a lynch mob did not form. He was promptly sent to Peterborough jail to await trial. Upon undressing him at the jail, the guards found that Brenton’s trousers under his grey clothes, were bespattered with blood.[32]

The Peterborough Times reported that the courthouse was packed “with the largest crowd ever seen within its walls”.[33] Drs. Kincaid and Sullivan both examined Brenton and told the judge that he was fit for trial even though he was “feigning madness”. The court called in Dr. Dickson, Medical Superintendent of the Rockwood Lunatic Asylum in Kingston, to interview Brenton and determine his sanity. He agreed with the local doctors that Brenton was “shamming mad”, but also wanted more time to examine him. It wasn’t until the 1873 Fall Assizes that Brenton’s trial began.

Brenton pleaded not guilty to the first-degree murder of Jane Payne. During the trial, numerous neighbours testified to the whereabouts of Brenton that day, as well as his behaviour. Jeremiah Payne testified that he did not believe Brenton was worth the $16 a month he gave him to work, but that his father-in-law suggested that amount. He told the court that there was a time that Brenton became paranoid that someone, or something, had put hairs in the flour in the home, and that the bread with hairs in it made him have worms in his stomach. Payne said that was impossible because his family ate the same bread and had no issues. Otherwise, Payne stated that he never thought Brenton was a threat.[34]

W.H. Ellis a professor of Chemistry at the School of Technology Toronto, testified that he studied the blood stains on Brenton’s pants that were taken off of him at the jail. He testified that they were blood droplets. Although Ellis could not determine whether the blood droplets were human or not, Jeremiah Payne was cross-examined numerous times regarding Brenton’s work on the farm and how he never killed any animals for him or his father-in-law. After numerous witnesses for the Crown and defence, the jury went away for deliberation. After less than an hour, they returned with a verdict: Guilty. Judge Wilson sentenced Brenton to be hanged on December 11, 1873.

Brenton, aka James Fox, was hanged in the Peterborough County Jail yard on December 26, 1873.[35] His execution was the first to occur in the Peterborough County jail. He was buried in the jail yard until 1995 when the remains of the four executed inmates buried in the jail yard were archaeologically excavated and moved.

Norman Henderson

On January 28, 1910, 74-year-old Margaret McPherson, and her sister, 60-year-old Susan McPherson were attacked in their Asphodel home by 17-year-old Norman Henderson over a 10-cent meal the women provided him. He had come around the neighbourhood asking for a meal and the women obliged. After he asked how much the dinner cost, one of the women responded “ten cents”. He placed the coin on the table and walked out. Ten minutes later, Henderson brandished an axe against the elderly women. Margaret sustained blows to her skull and brain tissue. On February 20th, Margaret succumbed to her injuries.[36]

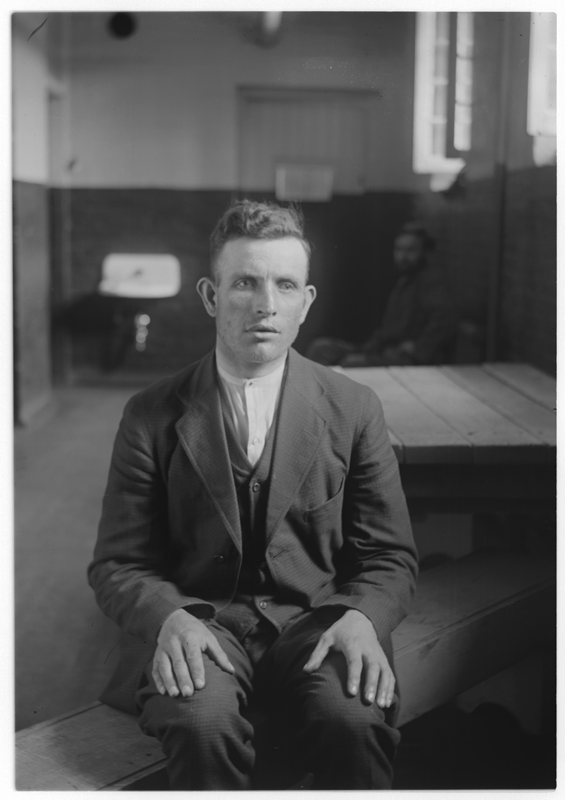

On March 31st, Judge Riddell sentenced Henderson to be hanged. The judge and jury believed there would be clemency, but Henderson was seen as a degenerate and was not granted a commuted sentence. Usually, there was clemency sought for people under 18 years of age who were sentenced to death. Henderson had only been in Canada since May 1909. He immigrated from England and worked on farms in Toronto and Peterborough until the murder. He was also wanted by Toronto police for theft and was deemed to be indifferent to right and wrong by psychiatrists.[37]

At 7:30 a.m. on June 24, 1910, Norman Henderson was hanged in the Peterborough County jail yard.[38] Former Peterborough Examiner reporter Ed Arnold wrote about the crime, trial, and execution in his book, Young Enough to Die, published in 2016. [39]

Michael Bahri and Thomas Kornchek

In June 1919, five Ukrainian/Russian men who resided in Toronto planned to take the midnight train to Havelock to gamble with the nearby Ontario Rock Company workers to win some money. Thomas Kornchek, Michael Bahri, Samuel Zilusky, Philip Rotyuski, and Alexander Martynuk arrived at the bunkhouses of the quarry workers and decided to rob the quarrymen instead of gambling. One of the men had “accidentally” shot off his revolver. It was argued that the revolver went off by itself and the shot was unintentional. The bullet hit Macedonian immigrant quarry worker, Philip Yannoff. He lived for 45 minutes, during which he asked for water but the men beat him. Judge Mulock sentenced all five men to be hanged on January 14, 1920. The jury gave recommendations of mercy for all five. However, only three of the men would be spared from the gallows.[40] The Toronto Star reported that in the Peterborough County jail, three of the guilty men were kept on one side of the building while Bahri and Kornchek were in cells on the opposite side of the jail.

Thomas Kornchek and Michael Bahri were hanged at the Peterborough County Jail at 8:30 a.m. on January 14, 1920.[41] Their bodies were buried in the jail yard. In 1995, their remains were exhumed and examined at the University of Western Ontario. Their bones were then buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood National Cemetery.[42] The other men were sent to Kingston Penitentiary for life sentences.

Edward Franklin Jackson

In June 1932, two Milwaukee-born African American men, 65-year-old Eugene Lee and 43-year-old Edward Franklin Jackson, travelled over the Canadian border at Sault Ste. Marie. They settled on land behind William Saltern’s farm in Douro-Dummer with plans to co-own a house, fruit trees, and chicken coop.[43]

It was going well in the warmer months, until Lee, whom community members began to call “Captain” due to his status as a veteran of the Spanish-American war, had become deeply engrained in the Saltern family dynamic. As the autumn weather rolled in, Lee told his partner that he was not able to acclimate to Canada’s cold, and began to sleep in the Saltern home. Jackson slept in the pairs’ car on their plot of land nearby.[44]

On October 17, 1932, Jackson went to the Saltern household to discuss Lee’s inaction regarding his portion of the building materials, building activities, and planting of fruit trees. For weeks, Lee had only come to the plot where the house was to be built once a week. The men had dug the space for a foundation by hand, which was an arduous task. Now, Jackson wanted clear-cut answers about the cement materials for the foundation and Lee’s promise to help out.[45] Harry and Ruby Saltern, members of the household, went inside to allow the men to talk privately until they both heard gunshots. Lee had been struck by six bullets from Jackson’s pistol. Jackson sat down and waited for police to arrive, while Harry drove to Crowe’s Landing to call for them.

Lee was buried in an unmarked grave in Lakefield Cemetery.[46] The Saltern family he had become close to did not attend his funeral.[47]

In Peterborough, Judge Sedgewick called upon numerous members of the Saltern family to give testimony as to what occurred the day of Lee’s murder. All witnesses and jury members were local, white, Canadian citizens. Judge Sedgewick did not ask Jackson to take the stand. Jackson was calm and complied with police officer David Silvester’s investigation and arrest. Silvester gave his testimony at the trial. After two and a half hours, the jury returned with a guilty verdict. Judge Sedgewick sentenced Jackson to be hanged on May 5, 1933. However, Jackson’s defence lawyer, G.N. Gordon, filed for appeal. Newspapers across Canada focused on Jacksons’ race in headlines such as “True Bill Against Negro”, “True Bill Against Peterborough Negro”, “Negro Sentenced to Hang for Ontario Murder”, and the disturbingly blunt “Negro Must Die” to racialize criminal activities in Canada.[48] Most of the newspapers also focused on the quarrel between the men over the cement for a chicken coop, even though the cement was for the house foundation. It was an act by the media to belittle and lessen the importance and livelihoods of both the victim and the accused.

Jackson’s appeal went to Osgoode Hall in Toronto, and a re-trial was set for September in Peterborough. Gordon argued that the case for murder over manslaughter rested upon 11-year-old Ruby Saltern’s testimony and that a miscarriage of justice had been at play. Justice Mulock asked why Jackson was armed on the day of the murder. Gordon responded “Men often go around armed in that country. It is in the wilds north of Peterboro.”[49] Gordon argued that Lee reached for his pistol first and that Jackson’s shots had been in self-defence, yet, Justice Sedgewick never allowed Jackson to give these details in court in Peterborough. The only testimony given in Peterborough was by white, local witnesses to the twelve white, local jurors.[50] Therefore, Gordon wanted the sentence appealed. However, the court remained unmoved and Justice Eric Armour sentenced Jackson to be hanged.[51]

On November 29, 1933, Edward Jackson was hanged in the Peterborough County Jail yard where his body was also buried.[52] Jackson was the last person to be hanged in Peterborough. His body was removed in 1995 during an archeological excavation of the jail yard.

Women in the jail

The Peterborough County jail housed men and women across its 160-year span. Based on available records, the majority of women were remanded or charged for vagrancy. Being impoverished with nowhere to go was punished with jail time. Some women were jailed for being “insane” and transferred to asylums across Ontario.[53]

Instead of aiding these women and girls with financial aid, the convicts were usually sent to reformatories or sentenced to light sentences in the Peterborough County jail. On June 29, 1886, 13-year-old Jane Billings was held for 11 days at the County jail before being sent to the Mercer Reformatory for four years. What did the 13-year-old do? She was arrested for being a “common prostitute”. She likely had no other choice or was forced into the occupation by family members. Or 14-year-old Minnie King who was sentenced to three years in a Reformatory, and 17-year-old Ann Moore, who was sentenced to 30 days for being an “inmate of a house of ill fame” to name a few.[54]

Mrs. Arthur Johnston, a 67-year-old widow, was charged with keeping a house of prostitution in 1885 and sentenced to 21 days in the County jail.[55] Perhaps some of the teens and women charged with prostitution in Peterborough worked for her.

On November 27, 1891, 35-year-old Livina Storms was charged with vagrancy, but along with her, was her 9-year-old son William Henry, 8-year-old daughter Sarah, 7-year-old Minnie May, 4-year-old James Martin, and 1-year-olds Benjamin and Amanda Saforna who were also charged with vagrancy and sentenced to spend six months in the County jail. Was this mercy or punishment? Could no church or charity provide the family with housing throughout the winter?[56] What were conditions like for the children? We may never know.

Child murderer — George Green

In late October 1849, 11-year-old George Green murdered 5-year-old Margaret O’Connor with a field hoe while tilling potatoes in Emily Township.[57] They were both orphans living with Thomas and Eliza Rowan on their farm. George told people that a bear had attacked and taken the girl, but after two days of searching, her body was found partially covered at the end of an upturned tree root, with the bloodied hoe near her body. Her body was beaten and bloodied by the hoe. It was the Rowan’s hoe that they had given George to till the potatoes. Thomas Rowan told the court that he somehow instinctively knew that George lied about the bear and questioned him relentlessly about what he had done before they found her body.

George was taken to the Peterborough County Jail to await his trial. He is possibly the youngest person ever tried for murder in Canada. Eliza Rowan testified that George confessed this guilt to her after he arrived at the jail. He said he had never thought of hurting Margaret before, until that day in the potato field.

He was sentenced to be hanged on June 26, 1850, but on June 4th his sentence was commuted to life in Kingston Penitentiary due to his young age.[58] According to an Ottawa Citizen reporter in 1978 who investigated the historical murderer, Green died within months of his arrival at Kingston Penitentiary.[59]

Media

A poem “The Dummer Murder” was written by William Telford, the “bard of Smith Township” regarding Jane Payne’s murder, possibly in November 1872.[60] The lengthy poem ends with the following stanza:

We leave the prisoner to await his doom,

Whether to freedom or the gallows gloom;

To law and justice we will all agree,

If guilty, hang — if innocent, set free.

A song written by an anonymous inmate, called “Johnston’s Hotel”, was discussed with Ontario folk song collector Edith Fowke in the 1950s. She met the self-declared author, who said he wrote it in the 1930s (although he derived its tune from “The Mountjoy Hotel” and some lyrics from “The Banks of the Don”).

“Johnston’s Hotel” is a nickname for the Peterborough County Jail. The song references local magistrates, sheriffs, turnkeys, and other persons related to the jail. Mrs. Tom Sullivan of Lakefield sang the song for Edith Fowke who recorded it in March 1957. It appeared on the vinyl long-playing recording Folk Songs of Ontario, released by Folkways Records of New York City in 1958. The original recording remains stored in the Smithsonian Archives, Washington D.C.[61]

Chorus:

Johnston’s Hotel, Johnston’s Hotel,

Oh, they treat you swell, at Johnston’s Hotel.

On the banks of the Otonabee, there’s a nice little spot

There’s a boarding house there where you get your meals hot

And across from the Quaker comes a corn-flaky smell

To remind you you’re boarding at Johnston’s Hotel

Oh, the rooms up at Johnston’s, they are heated with steam.

The finest apartments I ever have seen.

The windows are airy and barred beside,

To keep the good boarders from falling outside

Chorus

Oh, the meals up at Johnston’s, you get such a hoard.

If you want to cut beefsteak, borrow a sword.

Ain’t much to look at, but oh it is swell.

Just to be boarding at Johnston’s Hotel

There’s old Johnny Dainard, not a bad cop you know

And old Billy Wigg, he ain’t bad also

There’s Pearcy and Puffin, and Mahar as well.

They’re looking for boarders for Johnston’s Hotel.

Chorus

Oh, you’re in front of Langley and he’s reading your charge

My darling young boy, you’ve been running at large.

Oh, you’re in front of Langley and the truth you must tell

And he gives you your pass up to Johnston’s Hotel.

If you want to spend some time in Johnston’s Hotel

Just ramble down George Street, raising blue hell

Dry bread and water won’t cost you a cent.

Your taxes are paid for, your board and your rent.

Chorus

Demolition of the Jail

In June 2001, twelve inmates rioted in the Peterborough County jail. It was alleged that the riot occurred over the refusal of the staff to give inmates new toothbrushes. Steve Clancy, president of the Ontario Public Services Employees Union Local 308, claimed that the inmates received new small toothbrushes at least once or twice a week.[62] At this time, the inmates mostly served short sentences, court remands, or were held for court sentencing or transfer.

During the riot, thousands of dollars worth of damage was made. The inmates smashed beds, sinks, toilets, and other furniture.[63] Due to the province’s plan to open two large jails to replace 20 county jails, the Peterborough jail ended its operations on December 11, 2001. In February 2016, the 174-year-old jail was partially demolished and the Peterborough County Heritage Jail Park was officially opened.[64] It had been abandoned since 2001 after Ontario moved inmates to larger correctional facilities such as Lindsay’s Central East Correctional Centre.

As of March 2024, the historical courthouse and its modern additions include the County of Peterborough local government offices, Ontario Family Courts, and Property Management Peterborough Inc.

[Photos taken on March 24, 2024 by Ancestry by Alicia.]

© 2024 Ancestry by Alicia

[1] Scobell also designed St. John’s Church in Peterborough, as well as the Frontenac County Courthouse and Registry Office in Kingston, Ontario.

[2] Peterborough County, “Brief History”, accessed on March 13, 2024, accessible on: https://www.ptbocounty.ca/en/exploring/brief-history.aspx

[3] Ontario Heritage Trust, “District Court House and Jail”, accessed March 13, 2024, online at: https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques/district-court-house-and-jail

[4] Hanson and Guerin, pg. 11.

[5] Erik Hanson and Jennifer Guerin, “Heritage Designation Brief: The Peterborough County Courthouse – Appendix A”, Peterborough Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee, January 2021, pg. 4.

[6] Ontario Heritage Trust, “District Court House and Jail”, accessed March 13, 2024, online at: https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques/district-court-house-and-jail

[7] Peterborough County, “Peterborough County Heritage Jail Park”, accessed on March 13, 2024, available online: https://www.ptbocounty.ca/en/exploring/peterborough-county-heritage-jail-park.aspx#Background

[8] Report from The Peterborough Examiner via The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, April 04, 1857, pg. 5.

[9] The Peterborough Times (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada), February 24, 1872, pg. 2.

[10] The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, June 23, 1934, pg. 10.

[11] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, April 08, 1939, pg. 20.

[12] The Calgary Albertan (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) Saturday, December 12, 1953, pg. 5.

[13] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, November 23, 1961, pg. 27.

[14] Logan Taylor and Laura Schindel, “The Hidden Secrets in the Walls of a Local Institution: A Documentation of the Peterborough County Jail”, Trent Community Research Centre, September 2016-April 2017, accessed on March 19, 2024, https://digitalcollections.trentu.ca/objects/tcrc-1239, pg. 22-23.

[15] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Wednesday, June 01, 1966, pg. 27.

[16] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Friday, May 22, 1981, pg. 1.

[17] The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, December 28, 1957, pg. 11.

[18] The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, June 18, 1898, pg. 8.

[19] The Daily Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Wednesday, July 08, 1914, pg. 2.

[20] Marmora History “Sellyeh returns to Peterboro Jail”, MarmoraHistory.ca, pg. 40, https://marmorahistory.squarespace.com/s/A-Likely-story-pages-21-60.pdf; The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, May 21, 1925, pg. 10

[21] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, May 09, 1929, pg. 9; The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Wednesday, June 12, 1929, pg. 12; The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, January 05, 1929, pg. 3.

[22] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Friday, April 04, 1941, pg. 1.

[23] The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) Friday, May 21, 1943, pg. 25.

[24] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, July 19, 1969, pg. 14.

[25] The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Friday, September 25, 1992, pg. 5.

[26] Jeremiah Payne’s lot was in North Dummer, concession 7 lot 30 on Gilchrist Bay just west of the Stoney Lake settlement. Their house was on the west side of the lot, about 70 yards north of the road, and faced south. Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Registrations of Marriages, 1869-1928; Reel: 3, pg. 223r; 1871 Canada Census, Year: 1871; Census Place: Dummer, Peterborough East, Ontario; Roll: C-9988; Page: 11; Family No: 39.

[27] Brenton was also reported as James Fox, insinuating that Brenton was an alias he used in the area. Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois, USA) Sunday, November 24, 1872, pg. 9

[28] The Peterborough Times (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada) November 23, 1872, pg. 2.

[29] Although the Ontario Death Registration noted his name as David, the newspapers called him William or Richard throughout their reports. Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: Ms935; Series: 4, pg. 446.

[30] Ibid, Chicago Tribune, November 24, 1872, pg. 9; Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Series: Registrations of Births and Stillbirths, 1869-1913; Reel: 4; Record Group: Rg 80-2, Image 8.

[31] The Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, November 16, 1872, pg. 2.

[32] The Peterborough Times, November 23, 1872, pg. 2.

[33] The Peterborough Times (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada) April 19, 1873, pg. 2.

[34] The Peterborough Times (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada), November 1, 1873, pg. 2.

[35] Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: Ms935; Series: 8, #007497.

[36] The Globe (1844-1936); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]01 Mar 1910: 7.

[37] The Windsor Star (WINDSOR, ONTARIO, CANADA), Friday, April 1, 1910, pg. 2.

[38] The Ottawa Journal (OTTAWA, ONTARIO, CANADA), Friday, June 24, 1910, pg. 3.

[39] Ed Arnold, Young Enough to Die (Online: Self-Published, 2016)

[40] The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) Friday, October 10, 1919, pg. 2; The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, January 08, 1920, pg. 4.

[41] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Wednesday, January 14, 1920, pg. 1.

[42] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Friday, November 09, 2012, pg. 5.

[43] Newspapers and typed accounts from the time of the murder and trial write William’s last name as Salter and Saltern. Both William and Harry Saltern (witnesses at Jackson’s trial) are in the 1921 Canada Census in Dummer. 1921 Canada Census. Reference Number: RG 31; Folder Number: 81; Census Place: 81, Peterborough East, Ontario; Page Number: 3

[44] Norwood Women’s Institute, Tweedsmuir Community History Collections (Stoney Creek, ON: Federated Women’s Institutes of Ontario), 1965-2000, p. 102.

[45] The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) Wednesday, October 19, 1932, pg. 2; The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Tuesday, October 18, 1932, pg. 13.

[46] The Expositor (Brantford, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, October 20, 1932, pg. 12.

[47] Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]. 20 Oct 1932: p. 4.

[48] Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]. 07 Feb 1933: 17; The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Tuesday, February 07, 1933, pg. 2; The Province (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Wednesday, February 08, 1933, pg. 20; Calgary Herald (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) Tuesday, October 31, 1933, pg. 5.

[49] Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]. 29 Nov 1933: 31.

[50] Norwood Women’s Institute, p 103.

[51] The Sun Times (Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, September 21, 1933, pg. 6.

[52] Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 471; Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]. 29 Nov 1933: 31.

[53] Peterborough Jail Registers (1876-1896). Fonds 179. Trent Valley Archives, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, Sarah Kelly, 1886, prisoner number 1194; Bridget Hourigan, 1888, prisoner number 1402; Mary Fincham, 1888, prisoner number 1405; Margaret Patton, 1890, prisoner number 1638; Meline Rivard, 1891, prisoner number 1725; Georgina Rivard, 1891, prisoner number 1726; Lou McPherson, 1891, prisoner number 1766; Mary Ann Hardy, 1891, prisoner number 1775; Mary Jane Easton, 1891, prisoner number 1790; Barbara Ryan, 1891, prisoner number 1828; Janet Hunter, 1892, prisoner number 1887; Ellen Heffernan, 1892, prisoner number 1895; Mary Jane Easton [again], 1892, prisoner number 1927; Mary Ann McGuire, 1892, prisoner number 2016; Elizabeth Brennon, 1893, prisoner number 2074; Selina Stephenson, 1893, prisoner number 2082; Margaret Condon, 1893, prisoner number 2132; Margaret Hicks, 1893, prisoner number 2134; Anne Jane Clysdale, 1893, prisoner number 2157; Blizard, 1878, prisoner number 221; Elizabeth Dorran, 1894, prisoner number 2264; Bridget Mahoney, 1895, prisoner number 2371; Catherine Galvin, 1895, prisoner number 2403; Bridget Jeffers, 1879, prisoner number 315; Helen Maloney, 1879, prisoner number 339; Eliza Evans, 1880, prisoner number 382; Julia B Newton, 1880, prisoner number 393; Mary Jane Sanders, 1881, prisoner number 508; Bridget English, 1881, prisoner number 529; Margaret Oakley, 1881, prisoner number 566; Sarah Shannon, 1882, prisoner number 658; Alice Morton, 1877, prisoner number 85.

[54] Peterborough Jail Registers (1876–1896). Fonds 179. Trent Valley Archives, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, Jane Billings, 1886, prisoner number 1167; Ann Moore, 1889, prisoner number 1442; Francis McClair, 1889, prisoner number 1443; Martha Johnston, 1891, prisoner number 1767; Mary Rilson, 1891, prisoner number 1825; May Wilson [or is this Mary again?], 1892, prisoner number 1917; Cyrenna Davis, 1892, prisoner number 1920; Florence Menzies, 1892, prisoner number 1941; Mary Graystock, 1892, prisoner number 1943; Mrs David Menzies, 1892, prisoner number 1946; Elizabeth Allen, 1892, prisoner number 1965; Louisa Taylor, 1892, prisoner number 2022 [again 2029, 2033]; Rose Elliott, 1892, prisoner number 2022 [again 2029, 2034]; Georgia Earle, 1892, prisoner number 2024 [again 2031, 2035]; Ella Futton, 1878, prisoner number 214; Hattie Lyons, 1893, prisoner number 2177 [again 2179, 2182]; Elizabeth Wood, 1894 [again 2333, 2397, prisoner number 2191; Eliza Ann Allison, 1894, prisoner number 2215; Minnie Easton, 1894, prisoner number 2288 [again 2290, 2292]; Margaret McCutchan, 1878, prisoner number 229; Lizzie Paine, 1895, prisoner number 2535; Jane Lennox, 1895, prisoner number 2536; Jane Root, 1879, prisoner number 281; Anne Brennan, 1877 prisoner number 55 [again in 1879, prisoner number 282]; Minnie King, 1881, prisoner number 539; Emily Jane Dafoe, 1881, prisoner number 542; Margaret Brennan, 1877, prisoner number 56; Mary Elizabeth Barnhart, 1883, prisoner number 798; Sarah None, 1877, prisoner number 93; Elizabeth Dafoe, 1877, prisoner number 94.

[55] Peterborough Jail Registers (1860s–1907). Fonds 179. Trent Valley Archives, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, Mrs. Arthur Johnston, 1885, prisoner number 1030.

[56] Peterborough Jail Registers (1860s–1907). Fonds 179. Trent Valley Archives, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1891, prisoner numbers 1853, 1855, 1856, 1859.

[57] The Globe (1844-1936); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]20 Nov 1849: 447.

[58] The Globe (1844-1936); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]28 May 1850: 254; Niagara Falls Review (Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, September 09, 1978, pg. 21.

[59] The Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada), Saturday, September 9, 1978, pg. 81.

[60] William Telford, The Poems of William Telford, (Peterborough: J.R. Stratton, Printer and Book-Binder, Examiner Office, 1887), pg. 80. https://books.google.ca/books?id=MP7zDbHCaUgC&lpg=PA80&ots=79knzAPLeZ&dq=%22William%20Telford%22%20Dummer%20Murders&pg=PA80#v=onepage&q=Dummer%20Murders&f=false

[61] The Toronto Star (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Saturday, June 21, 1958, pg. 28; https://backwoodsmen.bandcamp.com/track/johnstons-hotel-2

[62] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Thursday, June 28, 2001, pg. 13.

[63] The Sault Star (Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada) Tuesday, June 26, 2001, pg. 15.

[64] The Peterborough Examiner, “County jail walls to come down over next couple months to create new park”, The Peterborough Examiner, January 20, 2016, https://www.thepeterboroughexaminer.com/news/peterborough-region/county-jail-walls-to-come-down-over-next-couple-months-to-create-new-park/article_f0cf847b-bcf0-5447-9b0f-b32502543107.html?