Updated February 2024

Originally posted January 2023

By Alicia Bertrand, M.A.

Whether your family has been in Canada for hundreds of years, or you’re a first-generation Canadian, Black Canadians have numerous barriers to compiling family research.[1] Barriers such as institutionalized racism, a lack of representation in government documentation, a lack of representation in the histories of cities and towns, withholding information about racialized communities in predominately white newspapers and other Canadian media, and much more. The majority of records and collections held by archives across Canada were created by not only white agents of municipal, provincial, or federal governments but also by white historians and researchers. There is a lack of archival records created by and/or about Black people that describe their lives and experiences, causing an unfortunate gap in documented and lived histories in Canada.

Another barrier continues to be the Americanized focus of historical research and stories in the media. Canada had the television show Ancestors in the Attic (2006-2013)[2], while the United States continues to air Finding Your Roots (2012-present) (with specials African American Lives, and African American Lives 2)[3] and Who Do You Think You Are? (2010-present) airing on PBS and NBC respectively.[4] I LOVE Finding Your Roots and Henry Louis Gates Jr. but where is our Canadian content? Canadian media needs to acknowledge the lives and histories that Black, Indigenous, and people of colour have experienced in this country. Ancestors in the Attic should make a comeback and help Canadians research their family’s past. Finding Your Roots includes amazing genealogy story-telling for numerous African Americans, but they are all stories of celebrities’ family trees, not ordinary citizens. I highly recommend the show. Henry Louis Gates Jr. is an icon.

Genealogists like myself are more than eager to aid anyone in their search for their family tree. Whether you’re just starting your research, or continuing the search, this article is meant to be a starting guide to Canadian resources for Black Canadians working on their genealogy. The information is organized into a “Where to Start” section, searching for the past, a short introduction to Black Canadian history, Ancestry.ca Directories (subscription required to access), Federal and Provincial resources, and a section for first-generation Black Canadians. I hope you find a useful link, historical society to contact, or archival database, that aids you in your endeavour. If your search in Canada is exhausted, then you may have to turn to records in the United States. Local libraries and state archives are great resources, and librarians are only an email away! I’d like to thank my friend and Innisfil IdeaLAB & Library’s Special Collections Librarian, Kate Zubczyk for inspiring this article.

Where to Start:

Starting your family tree is easy, you start with yourself! Most family tree websites will let you create a family tree database on their site for free but charge for access to records. It’s a great starting point to digitize your research unless you want to keep it on paper. Ancestry.ca, FamilySearch.org, and MyHeritage.com are the three most popular. However, the records that are digitized are very Western-centric. Ancestry.ca has an Ethnicity search option for “African American” but this may not help with Canadian, Caribbean, or African countries.

After you enter your own data, such as full name, birth date, and birthplace, the second step is to add your biological parents’ information. If you do not know enough information about them, ask family members OR the tree website or a genealogist may be able to help. (Living persons are much more difficult to research as their records are still protected). If you want to research a guardian, step-parent, or other parental status figures in your life, go for it! Family tree research is about finding interesting information about the people you want to know about. I’ve worked on trees for friends, colleagues, and partners because it’s interesting, not because I’m related to them.

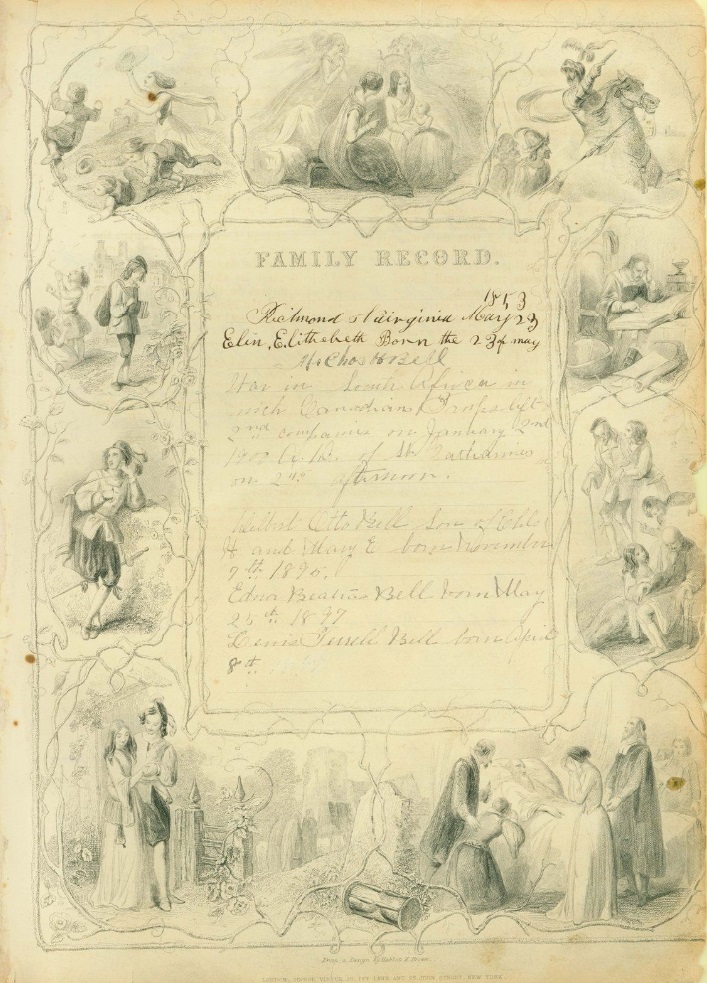

The next step is your grandparents. If you do not know their birth date or birthplace, enter as much information as you can, even if it’s just a name. If your older family members, such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, piblings, niblings,[5] and siblings, are still alive, oral history is the best resource for beginning a family tree. Ask the people in your family about their childhood, where they grew up, and what family members they spent holidays or birthdays with. Ask for photos. Was a family Bible kept? If your family has difficulty discussing their history, and you’ve hit a wall in your internet search, contemplate hiring a genealogist or paying for a family tree website membership that unlocks records.

A Short Introduction to Black Canadian History:

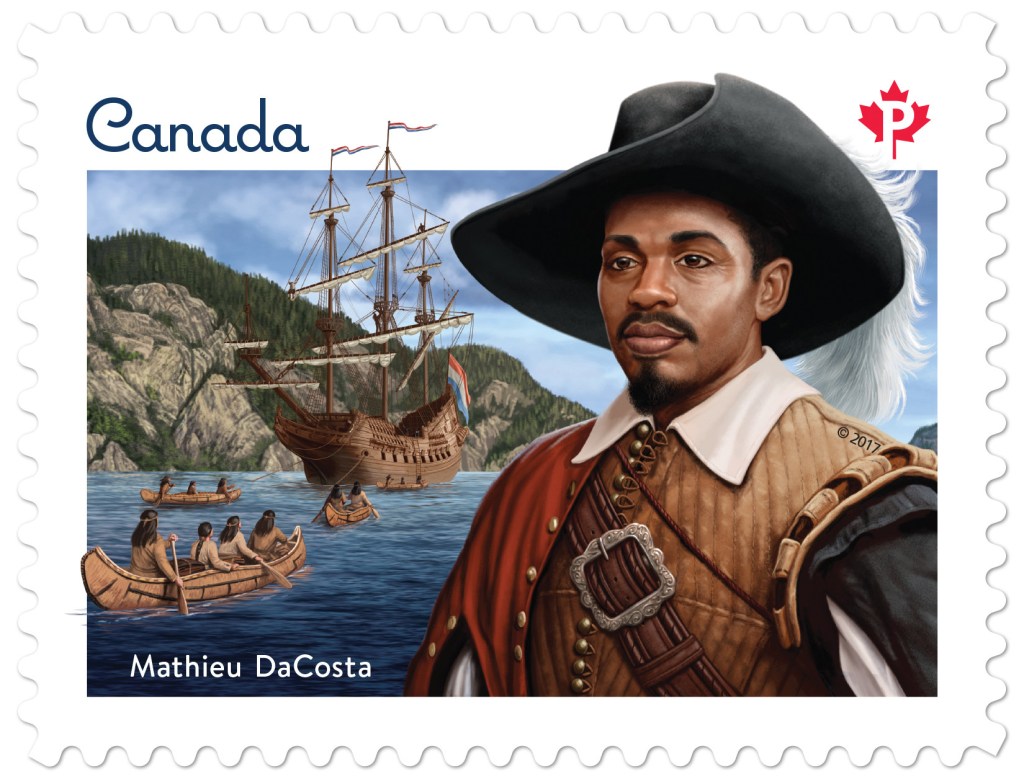

Throughout Canada’s history, there were multiple waves of Black immigration into Canada. The first, from 1763 on, included Black migrants fleeing enslavement in the United States. Although they were not the first Black people to live in Canada. The first (recorded) in Canada was an unnamed Black person who died of scurvy in Port-Royal, New France (modern-day Québec) during the winter of 1606–7, a possibility of Mathieu Da Costa, an interpreter for the Portuguese and Dutch, being in Acadia or the St. Lawrence Valley,[6] and in 1628, Olivier le Jeune was directly transported to New France from Madagascar. Although he was not recorded as a slave in records of the time, he was listed as a servant and was never free to leave Guillaume Couillard’s service.[7]

After the American Revolution ended in 1783, the British Crown gave passage to Canada to over 3000 slaves and free Blacks who had remained loyal to the Crown. Others were enslaved by white Loyalists who migrated to the Maritimes; therefore, over 5000 free and enslaved Black Americans migrated. Out of the 5000, one-third settled in New Brunswick.

In 1796, Jamaican Maroons were exiled to Nova Scotia. The Maroons were descendants of enslaved Black people who had escaped from the Spanish and Jamaica’s British rulers. After a number of years, the group worked on various public projects and found the poor provisions for their basic needs unacceptable in Nova Scotia. Therefore, they petitioned the government in order to emigrate. In 1800, hundreds of Maroons left Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone.

When researching your family tree, if you come across the term “Black Refugees” from 1813-1816, you should look into Nova Scotia and New Brunswick records of 2000 formerly enslaved people that fought for the British and sought settlement in Canada.

When the United States enacted the first Fugitive Slave Law in 1793, over 30,000 enslaved Black Americans came to Canada via the Underground Railroad until the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Most of them settled in southern Ontario. Regardless of the dangers and risks of recapture after the second Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Black Canadians participated in the Civil War to fight as free men against the Confederate Army. Due to Civil War regiments being racially segregated, people researching their family ancestry may find evidence of their Black Canadian ancestors in the United States Colored Troops records or in the U.S. Navy records. In conjunction with Civil War records, researchers can use the 1851 and 1861 Canadian Censuses which list race and place of birth, and some Census Enumerators even listed the State in which the person was born. Gaining any of these descriptive pieces of information is crucial to continue your research.

Side note: When researching data from Censuses in the United States and Canada, keep in mind that when Census Enumerators were taking people’s information, it was said out loud by the citizen, and written how the Enumerator heard it. Sometimes people would forget exactly what year they were born, or where. From Census to Census, your ancestor’s name spelling, birth year, and place of birth may change. This is normal. Don’t get discouraged! Keep a list of the spelling changes so that you can look for ALL spellings in different records.

In 1858, Sir James Douglas, on behalf of the British Crown, invited members of the San Francisco Black community to immigrate to British Columbia, and approximately 800 took him up on the offer.[8] Between 1897 and 1911, an influx of Black immigrants from Oklahoma to Alberta and Saskatchewan occurred. They were met with racist backlash, even government Order-in-Council measures to keep Black immigrants from coming to Alberta and Saskatchewan were approved, then appealed months later. In Saskatchewan, the largest black settlement was located in Eldon, and other settlements were created. By 1914, Black Oklahomans stopped migrating to the Prairies. Alberta’s Black Pioneer Heritage website delivers stories from these pioneer families to the modern day.[9] Black immigrants on the Prairies established towns, including Eldon, Amber Valley, Campsie, Keystone (now Breton), and Junkins (now Wildwood).

In the early 1900s Black immigrants were recruited from Barbados for the Dominion Coal Company in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. This community and their descendants are still present in Whitney Pier, Glace Bay, and New Waterford, Nova Scotia.

In the early 1900s, an influx of young women into Toronto caused concern for their safety, especially since most were single and away from their families. The YMCA housed these young Black women in Ontario House, at 698 Ontario Street, Toronto, Ontario. Black historian and archivist, Kathy Grant has compiled an in-depth history of Ontario House and other Black Canadian histories in Toronto.[10]

In the early 19th century, an influx of Black Americans came to Canada to work as railroad workers. Therefore, Black communities centred around train stations, such as Windsor Station in Montreal. Other communities emerged in Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, where Black districts with businesses and churches took root to meet the needs of porters and their families. Black Canadians helped shape Canada by working as porters for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Canadian National Railway (CNR), mostly in Pullman sleeping cars. In May 1945, after years of fighting for unionization, the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP), the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), and the CPR reached a collective bargaining agreement. The push for unionization, leading to better wages, reasonable hours, a week of paid vacation, overtime pay, and more, helped change Canada as they fought for equality for Black Canadians in the workplace.[11] The ExpoRail archives do not hold railway employee records but have a helpful document for those looking for ancestors working on Canada’s railways.

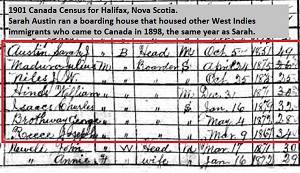

In 1955, Canada had a demand for domestic labour which led to the government’s introduction of the West Indian Domestic Scheme from 1955 to 1967. The scheme encouraged Caribbean women to migrate to Canada to become domestic workers in the homes of white families. After working for one year, they would be granted permanent residency and could bring other family members to Canada.

From 1963 to 1972, 3,539 Haitian political exiles immigrated to Montreal fleeing the Caribbean dictatorship of Papa Doc Duvalier. The Quebec government requested that the Government of Canada allow more French speakers into Canada, after which immigrants from French-speaking African and Caribbean countries came to Canada.[12]

These events do not cover all of the events and reasons for Black immigration to Canada, however, the background to understanding certain influxes may help you in your family search if your family came to Canada during one of these events. There is much more information and intricacies to the story that cannot be covered in one article.

Searching for the Past:

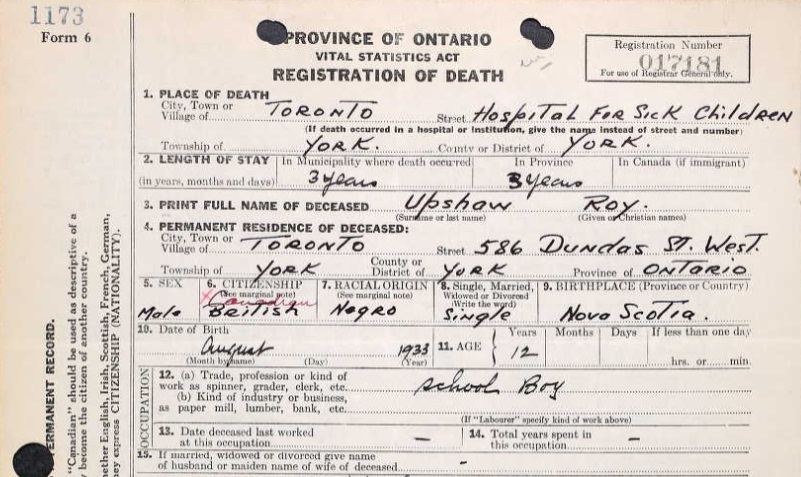

When searching digitized records, microfilm, or other sources for your ancestors, you may come across difficult and very outdated terminology, the main terms include “Black”, “coloured”, “mulatto”, “African” “negro”, or known country of origin. Other terms that may have been used include quadroon, octoroon, FPOC (free person of colour), mustee or griffe.[13] Keep in mind that although some terms are not currently acceptable descriptors, documents in Canada’s history may have used these words to describe the race of the person you are looking for.

The list of records that you can search for Canadian ancestors includes:

- Census records

- Land records

- Wills

- Runaway slave notices (mainly American-based records)

- Search and reward notices

- Vital records

- Manumissions (rare)

- Prison/jail records

- Tax/assessment records

- City directories (colourations of race/colour)

- Carleton Papers – Book of Negroes, 1783

- Military/militia records

- Newspapers

- Upper Canada sundries

- Church records

- Slave narratives

- Voting registrations

- Early Canadian books

- Government records

- Canadian Pacific Railway requests admission of coloured porters (Blacks), 1931-1949 (volume 577, file 816222, parts 6-10, microfilms C-10652 and C-10653) and Coloured domestics from Guadeloupe, 1910-1928 (volume 475, file 731832, microfilm C-10411).

Note: The names in these two files are indexed in this database: Immigrants to Canada, Porters and Domestics, 1899-1949. - Black Loyalist Refugees, Port Roseway Associates, 1782 to 1807

Ancestry.ca Directories:

Nova Scotia, Canada, Black Loyalist Directory, 1783 (approximately 3009 records)

Canada, CEF Commonwealth War Graves Registers, 1914-1919 (Over 50,000 records) They include some of the 2nd Construction Battalion (Canada’s first Black battalion from Nova Scotia) if they were buried on foreign soil.

Immigration & Emigration Books

- Former British Colonial Dependencies, Slave Registers, 1813-1834

Citizenship & Naturalization Records

Missionary enterprise among the coloured people of the Maritime Provinces of Canada, by the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Nova Scotia.

In the Ancestry.ca Search options, you can enter the racial descriptors listed above in this article, into the Race/Nationality text box. You can also use these terms in the Keyword text box of the Search options.

Example:

On May 5, 1946, 12-year-old, Nova Scotia born, Roy Upshaw died of tuberculosis at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. Below is a sample of his death certificate. His citizenship is listed as Canadian British. His Racial Origin is listed as Negro.

Federal Resources:

- Library of Archives Canada, Black Canadians, https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/collection/research-help/genealogy-family-history/ethno-cultural/pages/black-canadians.aspx

- Constance Backhouse, Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010)

- Paul Crooks, A tree without roots: the guide to tracing British, African and Asian Caribbean ancestry, (Mount Pleasant: Arcadia, 2008)

- Madeleine E. Mitchell, Jamaican Ancestry: How to Find Out More, Revised Edition, (Westminster: Heritage Books, 2008)

- Franklin Carter Smith and Emily Anne Croom, A genealogist’s guide to discovering your African-American ancestors: how to find and record your unique heritage, (Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 2003)

- African Canadian Heritage Association

- Black History in Canada

- The Provincial Freeman newspaper (digitized on Canadiana)

- Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada, (New York: Sheldon, Lamport and Blakeman, 1856) https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/drew/drew.html

- Daniel G. Hill Fonds

- Online Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, Black Loyalists

- The many works of Dr. Afua Cooper

- The Black Canadian Studies Association

- SlaveVoyages (includes Enslaved Databases separated into African Origins, and Oceans of Kinfolk)

Alberta:

- Chip Lake Historical Society, Where The River Lobstick Flows, (Wildwood: Chip Lake Historical Society, 1987)

- Rachel M. Wolters, “‘We Heard Canada Was a Free Country’: African American Migration in the Great Plains, 1890-1911”, (2017). Dissertations, http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/1483

- Alberta Provincial Archives

British Columbia:

- British Columbia’s Black Pioneers: Their Industry and Character Influenced the Vision of Canada

- Nanaimo African Heritage Society

- BC Black History Awareness Society

- Patricia H. Reid, “Segregation in British Columbia. The Committee on Archives of the United Church of Canada”, The Bulletin, Number 16, 1960 – 1963, pp. 1-15.

Manitoba:

New Brunswick:

- New Brunswick Black History Society

- University of New Brunswick Collections

- University of New Brunswick Libraries, “Exploring the Lives of Black Loyalists”, https://preserve.lib.unb.ca/wayback/20141205152154/http://atlanticportal.hil.unb.ca/acva/blackloyalists/en/

- County Council Marriage Records, 1789-1887

- Death Registration of Soldiers, 1941-1947

- Fredericton Burial Permit Listing 1902-1903; 1908-1911; 1915-1919

- Marriage Bonds, 1810-1932

- Saint John Burial Permits, 1889-1919

- Vital Statistics from Government Records

- Willow Creek

- Jordan Gill, “Historic Black settlement Willow Grove to be honoured by Canada Post“, CBC News, Nov 22, 2020.

Nova Scotia:

- Nova Scotia Archives, African Nova Scotians, https://archives.novascotia.ca/virtual/?Search=THans&List=all

- Birchtown, Nova Scotia Community

- African Nova Scotian Diaspora: Selected Government Records of Black Settlement, 1791-1839

- African Nova Scotian Settlement

- Africville Genealogy Society, The Spirit of Africville, (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 2010)

- Ruma Chopra, Almost Home: Maroons Between Slavery and Freedom in Jamaica, Nova Scotia, and Sierra Leone, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018)

- Peter Evander McKerrow, A Brief History of the Coloured Baptists of Nova Scotia, 1783-1895, Afro Nova Scotian Enterprises. 1976)

- Calvin W. Ruck, The Black Battalion 1916-1920: Canada’s Best Kept Military Secret, (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2016)

- Charles R. Saunders, Share & Care: The Story of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, (Halifax: Nimbus, 1994)

- Harvey Amani Whitfield, “Slavery in English Nova Scotia, 1750–1810“, Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol. 13, 2010, pp. 23-40.

- Census Returns, Assessment and Poll Tax Records 1767-1838

- Census Returns, 1767-1787

- Census Return, Granville, ‘1772 or 3’

- ‘Valuation Real Estate Halifax and surrounding areas 1775 and 1776’

- Assessments for Shelburne and outlying communities, 1786 and 1787

- Poll Tax Records, 1791-1795

- Census Returns, 1811, 1817 and 1818

- Census Returns, 1827

- Census Returns, 1838

- Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

- Carmelita Robertson, Black Loyalists of Nova Scotia: Tracing the History of Tracadie Loyalists, 1776-1787, (Halifax: Nova Scotia Museum, 2000).

- Black Halifax: Stories From Here

- Harvey A. Whitfield, Black American Refugees in Nova Scotia, 1813-1840, (Halifax: H. A. Whitfield, 2003), Dissertation.

Ontario:

- Ontario cities that had Black settlements that likely have information in city records and archives: Amherstburg, Colchester, Chatham, Windsor, and Sandwich, London, St Catharines, and Hamilton. Smaller communities in Barrie, Owen Sound and Guelph, and a Black district in Toronto.

- The Alvin McCurdy Collection[14]

- School petitions and correspondence for Black Canadian children to join white schools during segregation

[Students of King Street School in Amherstburg, Ontario with their teacher, J. H. Alexander, [ca. 1890s], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Reference Code: F 2076-16-7-4, Archives of Ontario, I0027815. Open copyright.] - Ontario Archives, Selected records pertaining to Black History in the Archives of Ontario, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/black_history.aspx#archival

- Ontario Archives, Online Exhibits, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/black_history.aspx#exhibits

- Ontario Archives, The Black Canadian Experience in Ontario: 1834-1914, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/index.aspx

- Voice of the Fugitive, 1851-1852 (Windsor) Newspaper

- Dawn of Tomorrow, 1932-1972 (Canadian League for Advancement of Colored People) Newspaper

- West Indian News Observer, 1967-1969 (Toronto) Newspaper

- Islander 1973-1975 (Toronto) Newspaper (see Toronto Public Library for microfilm)

- County of Simcoe, Researching Black History in Simcoe County, https://www.simcoe.ca/Archives/Pages/Black-History-Resources.aspx

- Elgin Settlement, Buxton

- Sharon Hepburn, Crossing the Border: A Free Black Community in Canada, (Illinois: University of Illinois, 2007)

- Linda Brown-Kubisch, The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black pioneers, 1839-1865, (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2004) – The settlement of the Queen’s Bush was located in a section of unsurveyed land where present-day Waterloo and Wellington counties meet, near Hawkesville, Ontario

- Griffin House

- The Wilberforce Street Settlement, Oro Township

- The Oro African Methodist Episcopal Church, built in the late 1840s, is one of the oldest African log churches still standing in North America.Reverend R. S. W. Sorrick

[Rev. R.S.W. Sorrick and family circa 1850, Oro Township, Ontario. Open copyright.]- Noah Morris

- The Oro African Methodist Episcopal Church, built in the late 1840s, is one of the oldest African log churches still standing in North America.Reverend R. S. W. Sorrick

- Pierpoint Settlement

- The Dawn Settlement

- Little Africa

- Amherstburg Freedom Museum

- Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society

- Karolyn Smardz Frost, Bryan Walls, Hilary Bates Neary, and Frederick H. Armstrong, Ontario’s African-Canadian Heritage: Collected Writings by Fred Landon, 1918-1967, (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2009)

- Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada

- Vanessa Warner, “Coloured Cemetery, Bertie Township, Welland County, Ontario“, Nov 29, 2008.

- Ontario Genealogical Society, “M004 1861 Census Black Heritage Grantham Township“.

- Marjorie Clark, “History Corner: Black Citizens of Early Puslinch“, Puslinch Today, September 11, 2016

- University of Calgary, “The Oro African Church: A History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Edgar, Ontario, Canada“, 1999.

- Colin Stephan McFarquhar, A difference of perspective, the black minority, white majority, and life in Ontario, 1870-1919. UWSpace: University of Waterloo Library, 1998, http://hdl.handle.net/10012/260

- Newspaper stories on The North American Convention of Colored Freemen held in Toronto from September 11-13, 1851 (newspaperarchive.com, newspapers.com, paid subscription required)

- Surnames found in the British Methodist Episcopal Church Cemetery

- The Walls Family Cemetery

- Our Ontario (contains newspaper articles and images from library and archive collections across Ontario)

- Vernon’s Directories (city directories that included name, employment, address)

- Canadian War Museum, A Community at War: the Military Service of Black Canadians of the Niagara Region, Special Exhibition until March 19, 2023.

Prince Edward Island:

- Jim Hornby, Black Islanders: Prince Edward Island’s Historical Black Community, (Charlottetown: Institute of Island Studies, 1991)

- Intercolonial Railway, Prince Edward Island Railways, and Canadian Government Railways Employees’ Provident Fund records (RG30): This sub-series includes staff books, 1855-1910, and service records cards on members of the Intercolonial and Prince Edward Island Railways Employees Provident Fund, 1855-1959. Railway Employees (Employees Provident Fund).

Quebec:

- Uhuru, 1969-1970 (Montreal) Newspaper

- BCRC Montreal, “Black Heritage and Historical Exploration” (Amazing excel file of literature and resources!)

- Cathie-Anne Dupuis, “Slavery as witnessed through New France’s parish registers“, Drouin Institute, November 2, 2020

- Généalogie Québec

- BAnQ, or Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec

- The Social Eyes, “Blacks in Quebec History: A Forgotten Legacy“, The Social Eyes, June 11, 2015

- Graeme Clyke fonds

- Leon Llewellyn fonds

- Maurice Tynes fonds

- Meilan Lam fonds

- Negro Community Centre/Charles H. Este Cultural Centre fonds

- Ralph Whims collection

Saskatchewan:

- Saskatchewan African Canadian Heritage Museum

- Shiloh Baptist Church

- Shiloh Baptist Church and Cemetery Restoration Society (Facebook group)

[Three generations of the Mayes family in front of the Shiloh Baptist Church they built. (Copyright permission from Leander K. Lane)]

- DeePVisions, “We Didn’t Know Our History,” I Am Black History, (Podcast)

- Carol Lafayette-Boyd, (Video) “Early History of African Descent People in Saskatchewan with Carol Lafayette”, University of Saskatchewan, February 10, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxWgzArmBjA

- R. Bruce Shepard, Deemed Unsuitable: Blacks from Oklahoma Move to the Canadian Prairies in Search of Equality in the Early 20th Century, Only to Find Racism in Their New Home, (Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1997)

- Ebele Mogo, “A Brief History of Saskatchewan’s Pioneering Settlers of African Descent”, Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society, August 5, 2020, https://www.skhistory.ca/blog/a-brief-history-of-saskatchewans-pioneering-settlers-of-african-descent

- Gail Arlene Ito, “The Quest for Land and Freedom on Canada’s Western Prairies: Black Oklahomans in Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1905-1912”, BlackPast.org. February 6, 2009, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/perspectives-global-african-history/quest-land-and-freedom-canadas-western-prairies-black-oklahomans-alberta-and-saskatchew/

Historical Societies:

- Africville Genealogy Society

- Afro-Métis Nation

- The Black Loyalist Historical Society

- African Descent Society BC

- AfriGeneas

U.S. Resources

A great list of resources has been compiled by Walter English for the Brister English Project. See bristerep.me for more details:

First Generation Black Canadians:

As a first generation Canadian, you may not need the sources listed in a Canadian context, but still want to begin a family tree. The best place to begin, after reading the “Where to Start” section of this article, is your parents’ birth country. You can always Google “[Country name] birth records”, “[Country name] Census”, “[Country name] death records”, etc. or hire a genealogist. FamilySearch.org has pages dedicated to certain records available by country:[15]

As of the 2016 Census, 52.4% of the Black population in Canada lived in Ontario. Close to half of Ontario’s Black population was born in Canada. Black immigrants in Ontario came from 150 different countries. About one-half were born in the Caribbean, with Jamaica representing 33.9%. Jamaican was also the most reported origin of those born in Canada. Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, Somalia, Ghana, and Ethiopia were the five other most reported countries for where citizens had immigrated from.[16]

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Aruba (formerly Netherlands Antilles)

- Bonaire (British Overseas Territory, formerly Netherlands Antilles)

- Curaçao (formerly Netherlands Antilles)

- Saba (Caribbean Netherlands, formerly Netherlands Antilles)

- Saint Martin, Saint Martin Island (French Antilles, France, northern 60% of the island)

- Sint Maarten, Saint Martin Island (Caribbean Netherlands, formerly Netherlands Antilles, southern 40% of the island)

If you have any other questions or comments, please reach out to me at alicia@ancestrybyalicia.ca. Good luck on your family research!

Disclaimer: The information in this article is current as of January 26, 2023. The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. The information is provided by Ancestry by Alicia and while we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Through this website, you are able to link to other websites which are not under the control of Ancestry by Alicia. We have no control over the nature, content and availability of those sites. The inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them.

[1] The term Black Canadian encompasses all people from the Caribbeans and mixed ethnicities, not just those of African descent. The term African American is also not appreciated among many Black Canadian groups, as they may not be African, nor American.

[2] Reader’s Digest and History Television, Ancestors in the Attic, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancestors_in_the_Attic

[3] PBS Publicity, “AFRICAN-AMERICAN LIVES, A Four-Hour Documentary Series Tracing Black History Through Genealogy and DNA Science, to Premiere February 2006 on PBS,” pbs.org, July 13, 2005, https://www.pbs.org/about/about-pbs/blogs/news/african-american-lives-a-four-hour-documentary-series-tracing-black-history-through-genealogy-and-dna-science-to-premiere-february-2006-on-pbs-july-13-2005/; PBS, African American Lives 2, pbs.org, https://www.pbs.org/show/african-american-lives-two/

[4] PBS, Finding Your Roots, https://www.pbs.org/show/finding-your-roots/; NBC, Who Do You Think You Are?, https://www.nbc.com/who-do-you-think-you-are

[5] Piblings and Niblings are gender-neutral terms for family members, such as your parents’ siblings, and your siblings’ child.

[6] Primary evidence is scarce; therefore, it is difficult to say whether he was in these areas of Canada, but he is celebrated by the Canadian government and communities as an early free Black explorer and interpreter. Dominique Millette and Maude-emmanuelle Lambert, “Mathieu Da Costa”, The Canadian Encycopedia, Edited December 19, 2016,

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/mathieu-da-costa

[7] Uchenna Edeh, Olivier Le Jeune: First African Slave Recorded Black In Canada, African Descent Society, May 10, 2016, https://www.adsbc.org/olivier-le-jeune-first-african-slave-recorded-black-in-canada/

[8] Black History in British Columbia, BC Archives, https://www.leg.bc.ca/content-peo/Learning-Resources/Black-History-in-BC-Fact-Sheet-English.pdf

[9] Heritage Community Foundation, Alberta’s Black Pioneer Heritage, http://wayback.archive-it.org/2217/20101208160316/http://www.albertasource.ca/blackpioneers/

[10] YMCA Toronto, “Ontario House: A place of refuge for Black women escaping abuse”, October 15, 2021, https://www.ywcatoronto.org/blog/Housing-History-

[11] Mel Toth, “How the Black Sleeping Car Porters Shaped Canada”, Cranbrook History Centre, https://www.cranbrookhistorycentre.com/how-the-black-sleeping-car-porters-shaped-canada/; C. Foster, They call me George: The untold story of black train porters and the birth of modern Canada, (Toronto: CELA, 2019); S. G. Grizzle, & J. Cooper, J., My names not George: The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: Personal reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle, (Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1998).

[12] The Social Eyes, “Blacks in Quebec History: A Forgotten Legacy“, The Social Eyes, June 11, 2015.

[13] https://www.archives.com/genealogy/family-heritage-african-american.html

[14] “Alvin McCurdy was a tireless collector of documentation about the lives and activities of the black people of south-western Ontario. His interests were both narrow and wide, extending from his own family history and genealogy, to the broader story of all the black families in and around Essex County. His collection includes physical evidence of all aspects of social, cultural and economic life, and his thorough research notes add a layer of valuable interpretation and insight.” Ontario Ministry of Public and Business Service Delivery, Images of Black History, Exploring the Alvin McCurdy Collection, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/alvin_mccurdy/index.aspx

[15] This is not a personal endorsement of FamilySearch.org or their religious background, their website simply has the easiest links to each country. It is operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Utah, United States.

[16] Statistics Canada, “More than half of Canada’s Black population calls Ontario home”, February 28, 2022, https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/441-more-half-canadas-black-population-calls-ontario-home

Hi Alicia,

One of the most informative articles I’ve seen. I am in need of connecting with a genealogist to assist in finding the connecting between my 4x grandfather (emancipated) and his parents who may have landed in Nova S. IN 1783.. any suggestions? Several attempts have been made of the course of 20 years…

LikeLike

Hi Chantal, thank you for reading! Email me at alicia@ancestrybyalicia.ca I can do some initial research for free to see if I can find anything more than what others have found over the years. I would be happy to help! Otherwise, the Ancestry website does have a “hire an expert” option, but that can get expensive really quickly.

LikeLike