Revolutionary War Ancestors

By Alicia M. Bertrand

March 18, 2025

Some Ontario residents may not realize that their ancestors arrived in Canada as United Empire Loyalists (UEL) who fled the American colonies or were granted land for military service in Upper Canada (now Ontario) or Lower Canada (now Quebec). During the American War of Independence, also known as the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), two groups fought for what they believed was their political right to property, livelihood, and freedom. In oversimplified terms, the Patriots wanted independence from the British Crown and government, and the loyalists did not want the colonies to separate from British rule. The Quakers in the United States were pacifists who attempted to avoid political turmoil. While researching your ancestors, be aware that sources from periods of war can be biased, exaggerated, or completely inaccurate. Even current sources on the Revolution, whether American or Canadian, harbour biased information and stories about each group. Use your best judgment and try to confirm specific stories or data before saving them to your family tree.

During the Revolution, more than 19,000 Loyalists served Britain in provincial military units, such as the King’s Royal Regiment of New York and Butler’s Rangers.[1] Some Loyalists had their property destroyed or taken over by Patriots, some were killed. Edward Hicks Sr. lost all of his property, cattle, and household goods. A militia took in Hicks and two sons as prisoners of war in New York. Hicks Sr. was hanged for treason. Jacobus Peek was imprisoned and was forced to forfeit his property.[2]

This article will summarize the details of my Revolutionary War veteran ancestors, including Edward Hicks Sr., Jacobus Peek, Aaron Bagg, David Miller, Simeon and Lazarus Puffer and William Carl. Most fought as Loyalists, and some fought for the Continental Army.

Descendants of UELs can join the United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada and apply for a Loyalist Certificate after proving their genealogical link to a UEL.

Descendants of the Patriots can join the Sons of the American Revolution or Daughters of the American Revolution.

Edward D. Hicks

Edward Hicks[3] was born on May 2, 1736 in Suffolk, New York, USA. There is controversy surrounding his parentage. There is a possibility that Isaac Hicks and Charity Edmonds are his parents. However, this is not confirmed.

Hicks married Elizabeth Lavina Elvina Cornell on January 19, 1758 in Hempstead, Long Island.[4] Together they had eight children: Benjamin, Edward, Mary, David, Joseph, Daniel, Elizabeth, and Joshua.

By 1775, the Hicks family lived in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania.[5] Hicks had purchased 600 acres of the Pennsylvania and Connecticut claims, a charter given to William Penn by King Charles II to grant land claims to residents between New York and Pennsylvania.[6] He had cleared about 25 acres of the land before the Revolutionary War began.

Hicks Sr. enlisted in the Second Regiment in Dutchess, New York, USA.[7] He joined the Butler’s Rangers and served under Capt. Walter Butler from December 25, 1777 to October 24, 1778.[8] According to the Pay Rolls of Butler’s Rangers 1777-1778, Hicks Sr. was paid £30, 8 shillings, at the rate of 2 shillings per day for 304 days of service.[9]

Hicks Sr. and his sons, Edward Hicks Jr. and Benjamin Hicks, were imprisoned by possibly the Westmoreland Militia outside Tioga, New York and taken to the Minisink Settlement.

Edward Hicks Sr. died on October 16, 1778 in Minisink, New York. Edward Hicks Jr. and Parshall Terry claimed that the Patriot militia hanged Hicks Sr. at the Minisink Settlement/Prison.[10] His body was never recovered for burial. However, Hicks Jr.’s testimony is the only evidence that Hicks Sr. was hanged. There is a story of Hicks Sr. being hanged on a tree outside of his son’s prison cell. After watching his father’s death, he knew he must escape or meet the same fate. He feigned illness and was granted fresh air outside of his cell, where he hit his guard over the head with his iron manacles and made a run for it.[11] Perhaps this tale is the exact story someone would tell their descendants. I will describe Hicks Jr.’s imprisonment and escape in more detail below.

Edward Hicks Jr. and his mother, now remarried as Elizabeth Elvina Wright, petitioned the British government and received extensive land grants in Marysburg, Prince Edward County, Ontario.

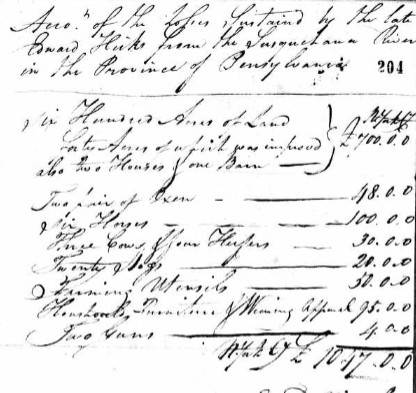

Hicks Jr. sent a property claim to the British government. He claimed that his fathers’ property was valued at £1047. The property listed included:[12]

| 600 acres of land, 40 acres of which was improved, also 2 houses and 1 barn | £700 |

| 2 pair of oxen | £48 |

| 6 horses | £100 |

| 3 cows and 4 heifers | £30 |

| 20 logs | £20 |

| Farming utensils | £50 |

| Household furniture and wearing apparel | £95 |

| 2 guns | £4 |

| Total | £1047 |

Edward Hicks Jr.

Edward Hicks Jr.[13] was born in 1761 in Albany, New York to Edward Hicks Sr. and Elizabeth Elvina Lavina (née Cornell).

Hicks Jr. followed his father into the British militia when the Revolutionary War broke out. Edward Hicks Jr. was listed as a Private in Captain William Caldwell’s Company of Butler’s Rangers. He was paid £30 and 8 shillings, at 2 shillings per day for 304 days of service from December 25, 1777 to October 24, 1778.[14]

Edward Hicks Jr. and Robert Land were taken prisoner on January 3, 1778. This is possibly the same instance in which Hicks Sr. was captured and killed. However, Land and Hicks were discussed in George Washington’s letters and correspondence to Washington from his Continental troops at Minisink.[15] There would be no reason to leave Hicks Sr. out of these discussions.

Hicks Jr. and Land were Court Martialed at the Continental troops prison in Minisink, New York. Hicks Jr. pleaded not guilty. As described above, Hicks Jr. allegedly devised a plan to feign illness to be allowed out of his cell. He was manacled and supposedly used them to his advantage to hit his guard over the head with them. He fled to a nearby stream where he found the nearby dam. The sheet of water that poured over the dam acted as a shield that Hicks Jr. used to conceal himself after an alarm had been made of his escape. He hid for 36 hours before he escaped through the woods. The tale even goes as far as to say he did not eat for nine days before he reached a British encampment.[16] It is likely that Hicks Jr. or his descendants greatly emphasized or imagined his harrowing escape from the Patriots. Caniff’s storytelling has no evidence other than possible word-of-mouth. He also states that Joshua Hicks, one of Edward Hicks Sr.’s 6 sons was part of the Butler’s Rangers alongside him. However, Joshua was only three years old when his father died. Edward Hicks Jr.’s brother Benjamin certainly did fight with the Butler’s Rangers, but the other sons were not listed.

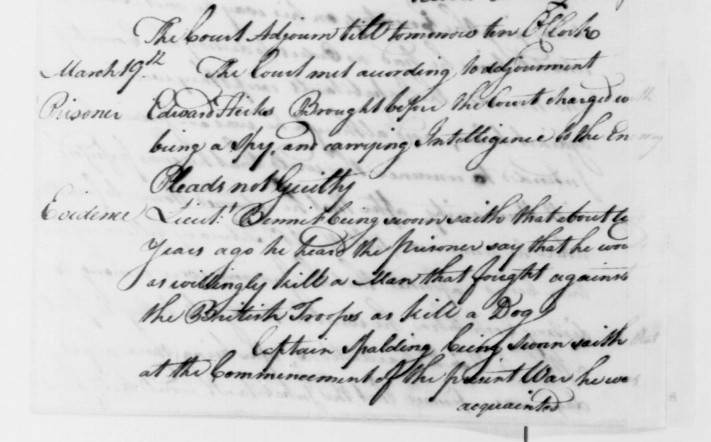

The court martial of Robert Hand and Edward Hicks took part from March 17-19, 1779 in Minisink, New York. Both men were charged with spying and carrying intelligence to Captain Butler and Joseph Brant.[17] Lieutenant Bennett testified that he heard Hicks Jr. say he would “as willingly kill a man that fought against the British Troops as kill a dog” [see image below].[18]

Hicks Jr. told his captors, perhaps as a way to not receive a death sentence, that he had attempted to return home under George Washington’s proclamation. He joined the British because he left his father’s house with 60 Torys [Loyalists] and went to Niagara for two months. [He was following his father and neighbours]. He entered Batteaux service for six weeks to take provisions from Niagara to Oswego. These travels took six weeks. That is when he heard George Washington proclaim that he would pardon anyone who had “joined the Indians” if they returned home. He said he immediately set out to return to Pennsylvania but was “too late” for the proclamation and the militia took him to Hartford, Connecticut and kept him prisoner until September 1778. He was sent to New York as a prisoner of war. He “entered into the service of the enemy in the Commissaries Department till the last day of February 79, when he made his escape from New York”. On his way to Niagara, he was taken by another militia near Corkithton[?].[19]

When he was sent to New York as a prisoner of war was his father with him then? He mentioned he escaped from New York and then was taken by another militia. Is this when he was captured with Robert Land?

Captain Eleazer Lindsey sentenced Edward Hicks Jr. to “close confinement” until the end of the war.[20] However, Hicks Jr. managed to escape.

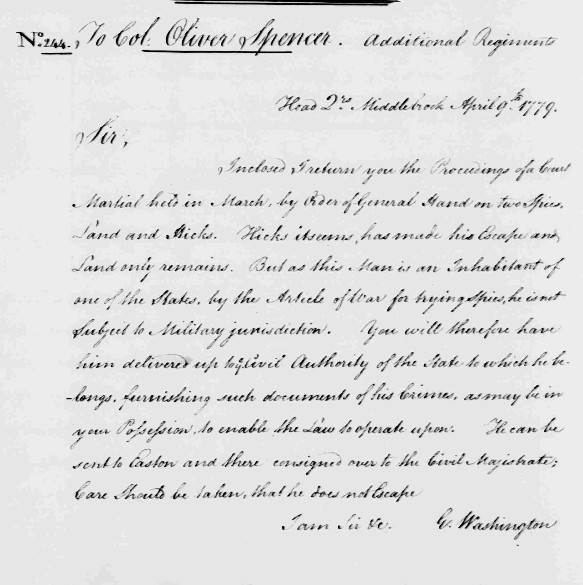

Upon learning of Hicks Jr.’s escape, George Washington wrote to Col. Oliver Spencer on April 9, 1779 that Robert Hands should be removed from Minisink prison and given to the civil magistrate, due to Hands being a citizen of Pennsylvania that is not under the current military jurisdiction. Washington finished the letter with, “Care should be taken that he does not escape.”[21] Hands did indeed escape, although he was wounded while he was chased by militiamen angered at his bail release as he and a group of Loyalists travelled to Niagara.[22]

After his escape, he was present at the Muster Roll on November 5, 1779. He was paid £377 and 3 shillings, which was the payment to Butler’s Rangers soldiers who had been imprisoned or killed in action.

He fled with his mother, brothers, and sisters to Canada. Hicks Jr. applied to the British government for money under a loyalist claim.

Hicks Jr. stated that he had lost the following property and goods to the Patriots in Pennsylvania:[23]

| 575 acres of bush land situated on the Susquehanna River | £575 |

| 25 acres improved land | £125 |

| Stock of cattle to the value of | £154 |

| Implements of agriculture | £10 |

| Household furniture and wearing apparel | £20 |

| New York currency total | £884 |

| Equal in starting to | £497 5 shillings |

He married Deborah Pringle in 1783 and had three children: John Hicks, Edward Hicks III, and Elizabeth Hicks. He and Deborah divorced in 1807 and then he married her younger sister, Esther, in 1816. He and Esther had four children: Solomon Pringle Hicks, Peter Hicks, William Hicks, and Timothy Thomas Hicks.

Hicks Jr. died on November 11, 1832 in South Marysburgh, Prince Edward County, after suffering with an illness for 10 days.[24] He is buried in the White Chapel Cemetery in Picton, Prince Edward County. However, in 2023, a volunteer searched for his headstone and could not find one.[25]

Lazarus Puffer

Lazarus Puffer[26] was born on June 1, 1729 to Eleazer Puffer and Elizabeth (née Talbott)in Stoughton, Norfolk, Massachusetts, USA.

He married Sarah Reynolds on November 12, 1753 in Lebanon-Goshen, New London, Connecticut, United States.[27]

Before fighting in the Revolutionary War, Puffer had served in the French and Indian War. He served in Captain Charles Dewey’s Company in 1757, then in Captain Edmond Well’s 5th Company, and Colonel Whitney’s 2nd Regiment between April 3 to October 26, 1758, and again in 1759. From April 5 to December 22, 1759, he was in Captain Ichabod Phelps’s company in 1760, 1761, and 1762.[28]

Puffer was a Private in Captain Silvanus Brown’s Company, 1st Brigade for the Rhode Island Regiment and the 8th Connecticut under Colonels John Chandler and Giles Russell for the Continental Army.[29]

Puffer was one of the Continental Army soldiers who followed George Washington to Valley Forge where the army established its third winter encampment from December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778.[30] George Washington ordered the men to build wooden huts, find straw to make beds, and attempt to stay warm. There was a lack of blankets for the 12,000 men and 500 women and children. An estimated third of Washington’s army at Valley Forge lacked proper footwear.[31] There were issues throughout the winter with the cold weather, lack of supplies, and spread of disease.

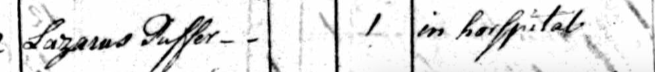

Although it does not state why, the Revolutionary War Muster Rolls listed Puffer as “in hospital” in December 1777. When he died in January 1778, the roll listed him correctly as “in hospital/died”. However, in the February, March, and April 1778 rolls, he continued to be listed as “in hospital”.[32] Were the rolls filled out incorrectly? Did the army not know who was who in the hospital? He was also listed as “discharged or deserted duty” before January 1, 1780, but he was deceased.[33] Out of the 12,000 soldiers and 500 women and children that accompanied the army at Valley Forge that winter, diseases such as influenza, typhus, dysentery and typhoid killed nearly 2,000 people. Perhaps Puffer died from one of these diseases.[34]

Puffer supposedly died on January 15, 1778 in Valley Forge, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, USA. However, Clarence Stewart Peterson stated in Known Military Dead During the American Revolutionary War, 1775-1783, that he had great difficulty researching the Revolutionary War dead due to fires and theft destroying original records in Washington, D.C. He relied on private collections and state military records in the National Archives.[35] He noted that Puffer died, and was not killed. This leads me to believe that he died of disease or from the cold, not an injury from battle.

He is allegedly buried in Valley Forge National Historic Park in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. However, National Park Service historian Joseph Lee Boyle, stated that no substantiated human graves have ever been found in the park.[36]

Puffer would not live to see the Continental Army leave Valley Forge and march into Monmouth, New Jersey to win an important battle for the American Patriots regardless of whether he died in January or April 1778.[37] Washington and the Continental Army moved out of Valley Forge in June 1778.

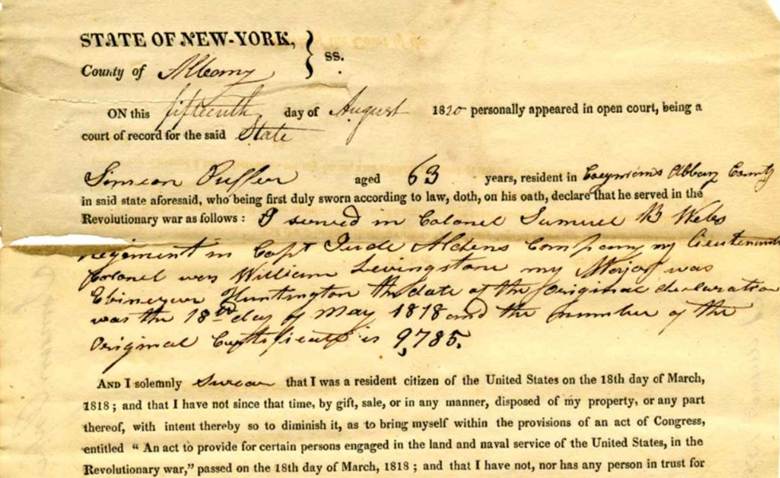

Simeon Puffer

Lazarus Puffer’s son, Simeon, also served in the Continental Army.[38]

Simeon Puffer was born in August 1759 to Lazarus Puffer and Sarah (née Reynolds) in Hebron, Tolland, Connecticut, USA.

Puffer served as a Private in Capt. Waterman’s Company, Lieutenant Colonel Obediah Hosford’s 12th Regiment. They marched to East Chester to join General Washington’s army.[39]

He was also a Private in Captain Judah Allen’s company in Lebanon, Connecticut, Colonel Samuel B. Webb’s Regiment from June 1777 to April 28, 1780. He was in Sullivan’s Expedition and several skirmishes. He served the Continental Army from February 1776 to December 31, 1780.[40]

After the war, he married Fanny Turner in 1784 in Fredericksburgh, Dutchess County, New York, USA.[41] They had the following children: Benjamin Puffer, Cornelius “Neil” Puffer, Sarah “Sally” Puffer, Harriet Puffer, James Simeon Puffer, and Hannah Puffer.

He was granted a pension for his service and his name was placed on the Pension Roll on April 25, 1819. However, there was some difficulty before his application for a pension was accepted. According to the Puffer Genealogy group, government officials questioned the legitimacy of his marriage to Fanny Turner. Simeon Puffer and Fanny were supposedly married by a Justice of the Peace and no records were filed. Numerous family and community members stepped forward to deliver affidavits. Due to their testimonies, the pension was granted.[42]

One of the witnesses was an elderly man, over 80 years old, Daniel Haynes. He signed an affidavit that stated he had known Fanny Turner since she was a girl. He witnessed Simeon Puffer come to court her after he was discharged from the Army. He worked for Nathan Sheldon as a labourer while Fanny lived there. Haynes stated that he saw Simeon and Fanny get married about 1794. He never saw them again after the Puffer couple moved to Albany, New York.

Daniel Dorman stated that he lived near Simeon in Coeymans, New York for about ten years. Dorman was told that Simeon’s wife and children moved up to Canada. He knew Simeon had stayed in New York and stayed with various friends at their residences. He would earn his pension, then travel to Canada to give the money to Fanny and the children. Dorman said Simeon refused to live in Canada with his family because of his hatred for the British.

Cornelius and Daniel Turner (Fanny’s brothers) stated that Fanny and the children moved to Canada around 1818. Simeon lived in Coeymans, New York and travelled around four times to Canada to deliver some of his pension money before his death.

Hannah DeGroat Turner (wife of Daniel Turner) stated in her affidavit that the Puffer children first moved to Canada. Their friends had persuaded them. Then, the children urged their mother to move to Canada, knowing that Simeon refused to move there. Hannah noted that on his last trip to see Fanny in Canada, he brought his pension for the family and a large family Bible for his wife and children. That trip was his last. Simeon became ill when he got to Fanny’s Canadian residence and didn’t get back to Coeymans. He died in Canada. Hannah testified that Simeon was “poor, but a good respectable man and lived happily with his wife and family.”[43]

Simeon Puffer died on June 16, 1825, while visiting his wife and children in Cramahe Township, Northumberland County, Ontario, Canada.

Jacobus Peek/Peak/Peeck

Jacobus Peek was born to Jacobus Peek and Rachel Demarest on May 21, 1738, in Schaalenburg, New Jersey, USA.

Not to be confused with Continental Army and Patriot, Jacobus Vedder Peek, Jacobus Peek was loyal to the British during the Revolutionary War.

Gregory Francis Walsh found that the Patriot residents of Bergen County would often continue their relationships with Loyalist neighbours. Bergen County was geographically close to the British garrison in New York City. This geography made it difficult for the New Jersey government to impress its authority onto its residents, especially while British troops, Loyalists, and merchants travelled easily throughout Bergen County throughout the Revolutionary War.[44] However, even the British Troops attacked and abused Patriots and Loyalists who were too elderly or unable to evacuate New Jersey and New York.[45]

Peek was imprisoned in July 1777 and was forced to forfeit his property in Hamilton Township, Bergen County, New Jersey.[46] He was again charged for joining the King of Great Britain and other treasonable practices” on January 26, 1779. The Commissioners of the Court of Common Pleas stated that if Peek and the other Loyalists named in the New Jersey Gazette did not appear before the court, the final judgment would be in favour of the state.[47]

His brother Samuel had an arrest order, but there is no record of imprisonment. His brother David had a tannery on his estate and had to sell his 122-acre estate for £1921. This was noted as a “grossly depreciated” value. When they surrendered to the American militia on January 13, 1783, any leftover possessions and land were taken.

Dr. W. K. Burr wrote that Jacobus and Samuel Peck were Captains in Britain’s “secret service” under Colonel Van Buskirk’s Regiment.[48] However, confirmation of this information is still required. William S. Stryker’s list of New Jersey volunteers does not include Jacobus or Samuel Peek, or variations of their last name, in Van Buskirk’s Regiment.[49] The Bergen County Historical Society notes that David and Samuel Peek were Captains in the King’s Militia Volunteers, but Jacobus is absent from the list.[50]

Jacobus, Samuel, and David took their families to Nova Scotia in 1784 as United Empire Loyalists to flee the United States.[51] Jacobus Peek’s son, Jacobus “James” Peek, married his first cousin, Samuel’s daughter Elizabeth Peek, on October 2, 1785, in Granville, Annapolis, Nova Scotia. This group of Peeks moved to Prince Edward County, Ontario and applied to be recognized as United Empire Loyalists due to their fathers’ loyalty to the British government. Since James and Elisabeth married as first cousins, Jacobus and Samuel are my paternal 6th great-grandfathers.

The families settled in Sophiasburgh, Prince Edward County, but supposedly, Jacobus and James returned to New Jersey in 1793 to attempt to receive compensation.[52] By 1795, they had returned to Sophiasburgh, where Jacobus Peek purchased Lot 22, Con. 1, west of Green Point.[53] William Canniff wrote that Samuel Peck was one of the first non-indigenous settlers of Big Island, just north of Sophiasburgh.[54]

In 1798, the Hon. John Elmsley, Esq., Chief Justice Hallowell, the Hon. James Baby, the Hon. Alexander Grant, and the Hon. David William Smith recommended 300 acres of land for Jacobus Peek as a UEL for serving the “Guides and Pioneers during the late American war”.[55]

Jacobus Peek died in Sophiasburgh, Prince Edward County, Ontario. According to certain online family tree resources, Peek died on May 30, 1803. Others state he died around 1817.[56] We need clarification from further research into death records, church records, etc.

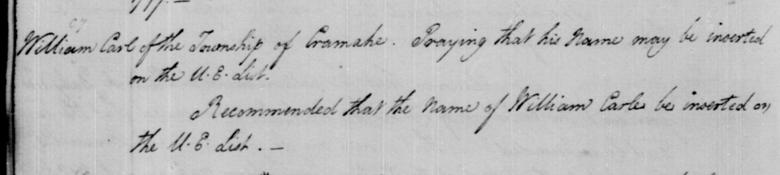

William Carl/Carle

William Carle[57] was born around 1735 in the United States. Certain Ancestry and WikiTree users believe William was born to Peter Krul and Maria Kershen, or James Carl and Catherine Johansen.[58]

Carl married Catherine Williams on February 28, 1768 in a Presbyterian Church in Rumbout, Dutchess Co., New York, U.S.A.

More than one William Carl(e) served in the Revolutionary War. It is difficult to determine what documentation belongs to the William Carl in question for this article. However, the documents regarding a William Carl who fought for the Continental Army would not be the Carl to whom this article pertains. It is possible Carl was part of the Seventh Regiment from Dutchess, New York, USA[59]

Due to his loyalty to the British Crown during the Revolutionary War, Carl was granted land in Brighton, Ontario. He received a plot next to his daughter Hannah and her husband, Daniel Masters.[60] On May 17, 1799, William Carle was listed on the “List of the Settlers in the Township of Cramahe” on plotNo 4 in 8th Con – about 10 acres clear.[61]

On January 9, 1807, J. McMucker, J.P. & Robert Young J.P. stated, “We certify that the bearer, William Carl came into this part of the province with his family in the year 1795 and has resided here ever since”.

On May 25, 1808, Carle was noted in the Upper Canada Land Petitions.[62] He requested that he be listed as a UEL.

On October 8, 1809, Carl was listed in the Upper Canada Land Petitions as living in Cramahe Township. He stated that he was a private in Col. Beverly Robinson’s Company. He received 200 acres and asked for 100 acres more to complete 300 allowed for “military lands”. His request was granted.[63] His sons, William Jr. and Joseph, were also petitioned for 200 acres each as sons of a UEL.[64] In The History of the Village Of Codrington, Dan Buchanan states that Carl’s acreage was in what would later be the village of Cramahe Hollow.[65]

The land granted to Carl was sold in 1809 to Eliakim Weller. It is unclear whether it was sold due to Carl’s death.[66] Daniel Masters sold land to Joseph Carl in 1812. William Carl signed as a witness to the transaction, but it does not specify whether it was William Carl Sr. or Jr.[67]

Aaron Bagg

Aaron Bagg[68] was born onSeptember 23, 1757 to John Bagg and Elizabeth Stocknell in Springfield, Massachusetts, USA.[69]

Bagg married Sarah Miller on September 27, 1775 in West Springfield, Massachusetts, USA.[70] Aaron and Sarah Bagg’s children included Nancy, John, and Lucy Bagg.

Bagg fought as a Private in the Continental Army. Bagg was listed in Captain Wheeler’s Company in August 1777 when they marched from Lansborough to Meloomscuyck.[71] Bagg only served for six days.[72] Captain [David] Wheeler was present at the Battle of Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775. The battle was the first offensive victory for American Patriot forces in the Revolutionary War. The Patriots secured a strategic passage north to Canada, and capturing the fort gave them a larger cache of artillery.[73]

After the war, Bagg served the town of West Springfield as a Moderator in 1811, and a Selectman from 1808 to 1821 and 1823 to 1824.[74]

Bagg died on August 16, 1839 in West Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts, USA.[75] He is buried in Ashley Cemetery in West Springfield.

David Miller

Aaron Bagg’s father-in-law, David Miller, also fought for the Continental Army against the British.

David Miller[76] was born on March 10, 1736, to Thomas Miller and Sarah Meekins in Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts, USA.

He married Anna (née possibly also Miller) between 1754 and 1756. David and Anna had at least six children: David Miller Jr., Thaddeus Miller, Abraham Miller, Sarah Miller, Seth Miller, and Lucy Miller.

Miller was a Private in Captain Parmelee Allen’s Company for the Continental Army in Vermont.[77] He enlisted on July 15, 1778 and was discharged on December 3, 1778. He was paid £4, 14 shillings, 8 pence. He should not be confused with another David Miller, son of Christopher and Jane (née Vobe) Miller, who fought for the Continental Army from Williamsburg, Virginia.

Miller’s son Thaddeus also fought for the Continental Army. He was a Private in Capt. Jonathan Warren’s Company in Col. John Sergeant’s Regiment as part of the Vermont Militia. He received a pension for his service until he died in 1842.[78]

Miller took the Freeman oath in September 1779 in Windsor, Vermont.[79]

Miller died on May 7, 1808 in Marlboro, Windham County, Vermont, USA.[80]

Are you related to any of these Revolutionary War soldiers? Comment below if you are. We could be distant cousins!

[1] Bruce G. Wilson, “Loyalists in Canada”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, April 2, 2009 [Updated August 12, 2021], Accessed on February 16, 2025 at https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/loyalists

[2] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series I; Class: AO 12; Piece: 85, pg. 43; National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War; Record Group Title: War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records; Record Group Number: 93; Series Number: M881; NARA Roll Number: 672; National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War; Record Group Title: War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records; Record Group Number: 93; Series Number: M881; NARA Roll Number: 149; Jones, E. Alfred (Edward Alfred), The Loyalists of New Jersey; their memorials, petitions, claims, etc., from English records (Boston: Gregg Press, 1972), pgs. 298-299; Birk, Hans Dietrich, and Mérey, Peter Béla, Armorial Heritage Foundation, Heraldic/Genealogical Almanac (1988) (Toronto: Pro Familia Pub, 1988) pg. 208.

[3] My 5th great-grandfather.

[4] Adventures for God: a history of St. George’s Episcopal Church, Hempstead, Long Island, pg. 170

[5] Alexander Fraser, [United Empire Loyalists] Second Report of the Bureau of Archives for the Province of Ontario, Volume XIV – Montreal, 1788 (Toronto, Canada L. K. Cameron, 1905), pg. 480.

[6] Ibid; Louise Welles Murray, A history of old Tioga Point and early Athens, Pennsylvania, (Athens: Louise Welles Murray, 1908), pg. 259.

[7] Ancestry.com. New York Military in the Revolution Dutchess County Militia (Land Bounty Rights) — Second Regiment, originally published in 1897 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2000.

[8] Ernest Cruikshank, The story of Butler’s Rangers and the settlement of Niagara, (Welland: Tribune Printing House, 1893 (Reprint 1975)), pgs. 116 & 119; William A Smy, An annotated nominal roll of Butler’s Rangers 1777-1784: with documentary sources, (Welland: Friends of the Loyalist Collection at Brock University, 2004), pg. 104.

[9] The Niagara Settlers webpage, “Soldiers and Supporters “H”” Accessed on February 16, 2025 on https://sites.google.com/site/niagarasettlers/soldiers-and/soldiers-h?authuser=0

[10] The Old United Empire Loyalists List, Appendix B, (Baltimore: Centennial Committee, 1969), pg. 192; The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series II; Class: AO 13; Piece: 080, pg. 204

[11] William Caniff, M.D., History of the Settlement of Upper Canada (Ontario), (Toronto: Dudley & Burns Printers, Victoria Hall, 1869), pgs. 104-105.

[12] The National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series 2; Class AO 13; Piece 080

[13] My 4th great-granduncle.

[14] Pay Rolls of Butler’s Rangers 1777-1778; Smy, pg. 103.

[15] Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Congress, February 11, 1779, Resolution on Court Martial, MSS 44693: Reel 056; George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army General Court Martial, Proceedings at Minisink, New York. March 17, 1779, pgs. 1-5. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Accessed on February 17, 2025, available online at: https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw453608/

[16] Caniff, pgs. 104-105.

[17] George Washington Papers, Series 4, March 17, 1779, pgs. 1-5.

[18] Ibid, pg. 3.

[19] Ibid, pg. 4.

[20] Ibid, pg 5

[21] George Washington Papers, Series 3, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Subseries 3B, Continental and State Military Personnel, 1775-1783, Letterbook 8: Jan. 1, 1779 – May 24, 1779″, March 17, 1779, MSS 44693: Reel 008, pg. 260.

[22] The Head of the Lake Historical Society, “The Story of the Land Family”, Wentworth Bygones – From the Papers and Records of the Head-of-the-Lake Historical Society, Hamilton, Ontario, Vol. 1 (Hamilton: Walsh Printing Service, 1958) Accessed online on February 17, 2025 at http://my.tbaytel.net/bmartin/rland.htm

[23] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series I; Class: AO 13; Piece: 044, pg. 8.

[24] Hallowell Free Press, 1830 – 1834, “Index to Marriages and Deaths”, Hallowell Press, November 20, 1832, available online at: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~saylormowbray/hallowellpress.html

[25] Find A Grave, “Edward “The Spy” Hicks”, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/236146145/edward-hicks

[26] My paternal 6th great-grandfather.

[27] Genealogical Publishing Co.; Baltimore, Maryland, USA; The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Town Vital Records. Vol. 1-55; Author: White, Lorraine Cook, Ed.; Publication Date: 1994-2002; Volume: 18, pg. 234.

[28] Connecticut Historical Society. Rolls of Connecticut Men in the French and Indian War, 1755-1762. Vol. I-II. Hartford, CT, USA: Connecticut Historical Society, 1903-1905.

[29] National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War; Record Group Title: War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records; Record Group Number: 93; Series Number: M881; NARA Roll Number: 343.

[30] Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. George Washington’s Headquarters at Valley Forge National Historic Park, whose land is split between Montgomery and Chester counties in eastern Pennsylvania. United States Valley Forge Pennsylvania Montgomery and Chester Counties Montgomery Chester Counties, 2015. -11-29. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2019688919/; Moran, Percy, Artist. Washington at Valley Forge / E. Percy Moran. United States Pennsylvania Valley Forge, ca. 1911. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92506172/; Dunsmore, John Ward, Artist. Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge/painting by Dunsmore. Valley Forge Pennsylvania United States, ca. 1907. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/91792202/; Mary Stockwell, Ph.D., “Valley Forge”, The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, Accessed on February 23, 2025, online at: https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/valley-forge

[31] “Washington’s Winters”, The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, Accessed on February 23, 2025, online at: https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/so-hard-a-winter#main-content

[32] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783; Microfilm Publication M246, 138 rolls; NAID: 602384; War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93, (Folders 129-131), Image 225, 228, 236, 242, 245 (April 1778), 341, 345; The National Archives in Washington, D.C; Valley Forge Park Alliance, Valley Force Muster Rolls, https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/soldier-details/; Clarence Stewart Peterson, Known Military Dead During the American Revolutionary War, 1775-1783 (Baltimore: Clarence Stewart Peterson, 1959), pg. 138

[33] Johnston, Henry P., ed., Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society Revolution Rolls and Lists, 1775-1783. Vol. VIII. Hartford, CT, USA: Connecticut Historical Society, 1901, 1999, pg. 90.

[34] Valley Forge National Historical Park Pennsylvania, “What Happened at Valley Forge”, Accessed on February 23, 2025, online at: https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/valley-forge-history-and-significance.htm

[35] Peterson, pg. 7.

[36] Independence Hall Association, “The Unsolved Mystery of Graves and Ghosts at Valley Forge”, Historic Valley Forge, Accessed on February 23, 2025, online at: https://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/history/vmyster.html?srsltid=AfmBOoqF-QqrqbTd3A_h7lGEpXDGM3JoeO0E7l9_Hm09_8pLirTsVRMr

[37] Ibid;

[38] My paternal 5th great-grandfather.

[39] Johnson, pg. 160.

[40] Johnston, pg. 90; The National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Ledgers of Payments, 1818-1872, to U.S. Pensioners Under Acts of 1818 Through 1858 From Records of the Office of the Third Auditor of the Treasury; Record Group Title: Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury; Record Group Number: 217; Series Number: T718; Roll Number: 17; Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (NARA microfilm publication M804, 2,670 rolls). Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[41] Descendants of George Puffer of Braintree, Massachusetts, 1639-1915, pg 71-72

https://archive.org/details/descendantsofgeo00nutt/page/72/mode/2up?q=fanny+turner

[42] https://puffergenealogy.info/getperson.php?personID=I33013&tree=tree1

[43] Ibid.

[44] Gregory Francis Walsh, Splintered Loyalties: The Revolutionary War in Essex County, New Jersey (PhD diss., The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Boston College, May 2011), pg. 206.

[45] Ibid, pg. 117.

[46] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series I; Class: AO 12; Piece: 85, pg. 43; National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War; Record Group Title: War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records; Record Group Number: 93; Series Number: M881; NARA Roll Number: 672; National Archives; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Soldiers who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War; Record Group Title: War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records; Record Group Number: 93; Series Number: M881; NARA Roll Number: 149; Jones, E. Alfred (Edward Alfred), The Loyalists of New Jersey; their memorials, petitions, claims, etc., from English records (Boston: Gregg Press, 1972), pgs. 298-299; Birk, Hans Dietrich, and Mérey, Peter Béla, Armorial Heritage Foundation, Heraldic/Genealogical Almanac (1988) (Toronto: Pro Familia Pub, 1988) pg. 208.

[47] New Jersey Gazette, 24 Feb 1779, Volume II, Issue 64, pg. 3, Accessed on March 2, 2025,

Transcribed online at: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~saylormowbray/loyalistbergen.html

[48] Dr. W. K. Burr, “For the Historical Society – James Peck No. 2”, 1929, newspaper clipping uploaded by Ancestry user MamaSinclair. Accessed online on March 2, 2025.

[49] William S. Stryker, Adjutant-General of New Jersey, “The New Jersey Volunteers” (Loyalists) in the Revolutionary War, (Trenton, N. J.: Naar, Day & Naar, Book and Job Printers, 1887).

[50] Braisted, Todd W. “Bergen County’s Loyalist Population,” Bergen County Historical Society. Accessed March 2, 2025. https://www.bergencountyhistory.org/loyalists-in-bergen.

[51] Loyalists and Land Settlement in Nova Scotia, Annapolis County (Grants), pg. 19.

[52] Jackson, Ronald V., Accelerated Indexing Systems, comp., New Jersey Census, 1643-1890. Compiled and digitized by Mr. Jackson and AIS from microfilmed schedules of the U.S. Federal Decennial Census, territorial/state censuses, and/or census substitutes.

[53] Birk and Mérey, online access without page number https://navalmarinearchive.com/research/docs/hallowell_elmsley_township.html

[54] Canniff, pg. 406.

[55] Birk and Mérey, online access without page number https://navalmarinearchive.com/research/docs/hallowell_elmsley_township.html

[56] Family Search, Jacobus Peck, Accessed online March 5, 2025, online at

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/LHTV-117; Trees by Dan, Jacobus Peck, Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://www.treesbydan.com/p5195.htm; RootsWeb, Shunk Family, Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~shunkfamilytree/genealogy/FamilyTree/Shunk%20Family/fam21410.htm;

[57] My paternal 5th great-grandfather.

[58] WikiTree, William Carle (abt. 1748 – abt. 1808), Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Carle-152; Ancestry user katrina lindsay, WILLIAM Carle or Carl, Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://www.ancestry.ca/family-tree/person/tree/168852331/person/112205864939/facts; Ancestry user Elva Patterson, William Carle, Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://www.ancestry.ca/family-tree/person/tree/3101419/person/-1461572959/facts

[59] Dutchess County Militia: Land Bounty Rights – 7th Regiment, Accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://www.americanwars.org/ny-american-revolution/dutchess-county-militia-seventh-regiment-lbr.htm; The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series I; Class: AO 12; Piece: 87, pg. 5

[60] Dan Buchanan, “First Settlers of Brighton”, October 23, 2012, pg. 23, accessed on March 5, 2025, online at https://danbuchananhistoryguy.com/uploads/1/1/5/0/115043459/firstsettlersofbrighton.pdf

[61] A list of the Settlers in the Township of Cramahe 13 May 1799, UCLP, RG 1 L3, 1799, V92, bundle C4/145, C-1649, online at LAC, starts at image 203

[62] Library and Archives Canada, Upper Canada Land Books – C-102, RG 1 L1, 205068, Vol. 23-27, image 706, Accessed on March 6, 2025, online at

https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c102

[63] Library and Archives Canada, Upper Canada Land Books – C-102, RG 1 L1, 205068, Vol. 23-27, Image 729, Accessed on March 15, 2025, online at

https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c102

[64] Ibid, image 947.

[65] Buchanan, Dan. The History of the Village of Codrington. May 2018. Accessed on March 15, 2025. http://danbuchananhistoryguy.com.

[66] Margaret McBurney and Mary Byers, Homesteads: Early Buildings and Families from Kingston to Toronto (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979), pg. 47.

[67] Archive photo from unknown source uploaded by Ancestry user jenkanderson. Accessed on March 15, 2025.

[68] My maternal 7th great-grandfather.

[69] Find A Grave, “Aaron Bragg”, Accessed on March 15, 2025, online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62842803/aaron-bagg

[70] New England Historic Genealogical Society. The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Boston: The New England Historic Genealogical Society, pg. 56.

[71] Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970. Louisville, Kentucky: National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Microfilm, 508 rolls, slide 307-310; Godfrey Memorial Library. American Genealogical-Biographical Index. Middletown, CT, USA: Godfrey Memorial Library, Vol. 7, pg. 87.

[72] Wright & Potter Printing Co., Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, vol. 1 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., n.d.), pg. 439.

[73] American Battlefield Trust, Fort Ticonderoga, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/fort-ticonderoga-1775.

[74] Bryan’s Gravestone Restoration, Facebook post, “John Bagg (Before),” October 23, 2022, accessed March 15, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=641581407623911&id=106862634429127&set=a.140371211078269&locale=nn_NO.

[75] Find A Grave, “Aaron Bragg”, Accessed on March 15, 2025, online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62842803/aaron-bagg

[76] My maternal 8th great-grandfather.

[77] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783; Microfilm Publication M246, 138 rolls; NAID: 602384; War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93; The National Archives in Washington, D.C; John E. Goodrich, ed., The State of Vermont. Rolls of the Soldiers in the Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783, (Rutland: Tuttle, 1904), pgs. 49-50.

[78] United States Senate. The Pension Roll of 1835.4 vols. 1968 Reprint, with index. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992; Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783; Microfilm Publication M246, 138 rolls; NAID: 602384; War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93; The National Archives in Washington, D.C.

[79] Ephraim H. Newton, The History of the Town of Marlborough, Windham County, Vermont (Montpelier: Vermont Historical Society, 1930), pg. 108.

[80] New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; State of Vermont. Vermont Vital Records through 1870, image 2319.

Fabulous post. I am certainly going to be checking out some of those links provided in the footnotes. Also, any author writing a novel about the American Revolution needs to include Lazarus Puffer (great name.)

LikeLike

Thank you Mark! Lazarus is certainly one of the coolest names.

LikeLike